Background

The EU’s sustainability framework has seen significant turbulence throughout 2025. After the EU Commission introduced two Omnibus packages in February, one Omnibus to ‘stop the clock’ to postpone key reporting deadlines for the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD), and a second Omnibus aimed at reducing compliance burdens by at least 25%, the legislative process quickly became a battleground for competing priorities (please be referred to our earlier publication). The Council adopted its Final Position in June 2025 (please be referred to our earlier publication), but momentum stalled in October when the EU Parliament unexpectedly withdrew its support for trilogue negotiations (please be referred to our earlier publication), reopening fundamental debates on the scope and ambition of the reforms. The EU Parliament adopted its final position in November 2025 (please be referred to our earlier publication).

Intense negotiations followed, culminating in a last-minute provisional agreement between the EU Legislator on 9 December 2025 (the Final Omnibus). This Final Omnibus text, as formally endorsed today on 16 December 2025 by the EU Parliament sets the stage for a new phase in EU sustainability regulation: one that promises simplification and reduced administrative burden but also raises critical questions about the future direction and effectiveness of the EU’s corporate sustainability agenda.

This blog is based on the official Final Omnibus text as published by the Council of the EU and formally endorsed today by the EU Parliament on 16 December 2025. While minor technical adjustments may still follow, the analysis below provides an overview of the key principles and obligations as they currently stand.

The Final Omnibus text of the CSRD

Companies in-scope under the CSRD

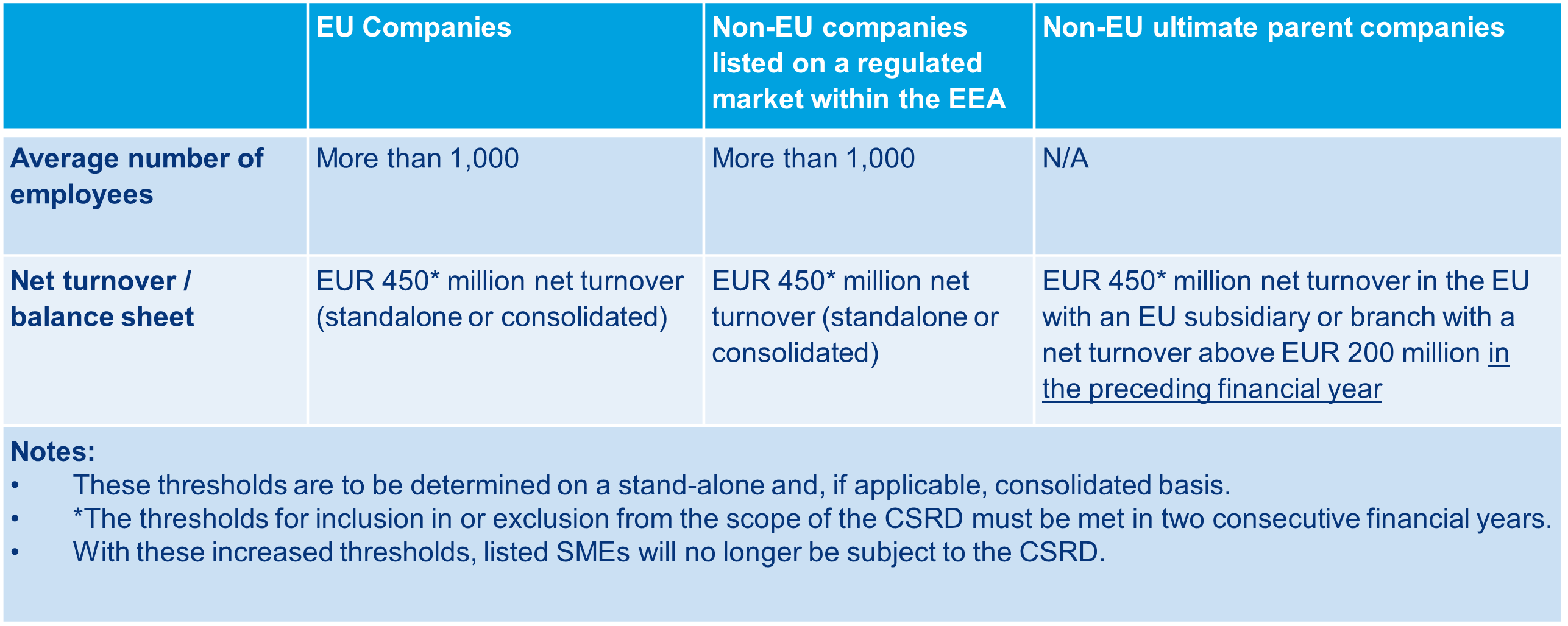

The Final Omnibus significantly narrows the scope of the CSRD to the type of undertakings set out in the table below. The value chain cap is set at 1,000 employees, and there are new, explicit protections for smaller suppliers. Financial holding undertakings with diverse, independent subsidiaries are now exempt from consolidated reporting.

The Final Omnibus grants EU Member States the discretion to exempt existing “wave 1” undertakings from CSRD obligations for the financial years 2025 and 2026. This option applies to companies that qualified under the previous thresholds for wave 1 (e.g., more than 500 employees and either a total assets of EUR 25 million or net turnover of EUR 50 million and classified as a public interest entity, or such non-EU undertakings listed on a regulated market within the EEA) but would fall outside the revised scope of more than 1,000 employees following the Final Omnibus. The measure is intended to prevent a sudden withdrawal from the regime, allowing former wave 1 undertakings time to adapt, although it may create temporary divergence across the EU as implementation of this transitional provision is left to the discretion of individual Member States. After the transitional period, such undertakings will either exit the CSRD framework entirely or re-enter under the new criteria.

The Final Omnibus confirms the removal of the requirement for the EU Commission to adopt mandatory standards for “reasonable assurance” of sustainability reporting to avoid increased costs and complexity for undertakings.

What remains is the obligation for the EU Commission to adopt limited assurance standards by delegated act. Article 26a(1) requires statutory auditors and audit firms to carry out sustainability assurance in compliance with these limited assurance standards. The current deadline is 1 October 2026, although the recital notes that this may be postponed to 1 July 2027 to allow adequate time for development. This change is intended to reduce compliance costs and administrative burden while ensuring a harmonised approach to limited assurance across the EU.

The Final Omnibus addresses a key concern under Article 19a(3) of Directive 2013/34/EU: reporting undertakings must disclose information not only about their own operations but also about their value chain. Experience has shown that small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the value chain have often faced disproportionate information requests, despite existing limitations in Article 29b(4). To remedy this, the compromise introduces a “value-chain cap” and a set of protections for undertakings with fewer than 1,000 employees on average during the financial year (“protected undertakings”).

Under this new regime:

Reporting undertakings may rely on a simple self-declaration from value-chain actors to determine their size. No further verification is required unless the reporting undertaking knows, or can reasonably be expected to know, that the declaration is manifestly incorrect (recital 9 and Article 19a(3)).

Reporting undertakings are prohibited from requesting information beyond the limits specified in the voluntary sustainability reporting standards to be adopted by the Commission under Article 29ca. Protected undertakings have a statutory right to refuse any request exceeding those limits (recital 9 and Article 29ca).

If a reporting undertaking nevertheless seeks additional information, it must inform the protected undertaking both of the extra information requested and of its right to decline. The cap applies only to sustainability reporting under the CSRD; it does not affect voluntary sharing of sector-specific data, contractual obligations within the permitted scope, or due diligence and risk management processes unrelated to reporting (recital 9 and Article 19a(3)).

Undertakings that comply with these limitations are deemed to fulfil their reporting obligations under Articles 19a and 29a. Assurance providers must respect these protections when preparing their assurance opinion (recital 9 and Articles 19a and 29a).

Recognising that complete data may not always be available, the compromise allows reporting undertakings to use estimates or explain why certain information could not be obtained, without penalty, provided they act proportionately.

To support this framework, the EU Commission is empowered to adopt delegated acts establishing voluntary sustainability reporting standards for undertakings outside the mandatory scope (Article 29ca(1)). These standards must:

- Be proportionate and relevant to the capacities and characteristics of such undertakings and to the scale and complexity of their activities (Article 29ca(2)).

- Explicitly limit the scope of information that may be requested from these undertakings.

- Take account of legal and practical difficulties in obtaining data from the value chain, particularly from entities outside the CSRD or suppliers in emerging markets (recital 12a).

- Provide a structured template for voluntary reporting.

Until these delegated acts are adopted, undertakings may report in accordance with Commission Recommendation 2025/1710, based on the VSME standard developed by EFRAG (recital 16 and Article 29ca(2)). Both interim and future standards must use simplified language and allow flexibility and progression in disclosures.

Reporting undertakings must adopt a risk-based approach, prioritising efforts to obtain information on high-risk impacts and sustainability matters commonly associated with their sector. They shall not seek to obtain from undertakings in their value chain with fewer than 1,000 employees any information beyond what is specified in the voluntary standards for undertakings that are not required to report on sustainability, except for additional sustainability information that is commonly shared within the relevant sector (Article 19a(3)). Assurance providers must respect this limitation when preparing their assurance opinion (Recital 9).

Where information cannot be obtained due to legal or practical limitations, reporting undertakings are permitted to explain the efforts made to obtain such information, the reasons for its unavailability, and the plans to obtain it in the future. For the first three years of being subject to sustainability reporting requirements, such explanation is deemed to constitute compliance; thereafter, undertakings must meet the reporting requirements using information obtained directly or, where appropriate, estimates (Article 19a, transitional provision).

Sustainability reporting requirements under the CSRD do not oblige undertakings to disclose trade secrets, intellectual property, or know-how, in line with Directive (EU) 2016/943 (recital 9c and Article 29a(5a)).

Under the final compromise, Article 19a(1) of Directive 2013/34/EU has been amended to significantly narrow the scope of individual sustainability reporting. The obligation to prepare and publish a sustainability statement at individual level now applies only to undertakings with an average of more than 1,000 employees and net turnover of at least EUR 450 million during the financial year (Article 19a(1); recital 5). This represents a substantial reduction in the reporting burden for smaller entities. The same reduction in scope applies to credit institutions and insurance undertakings, regardless of their legal form.

Furthermore, ultimate parent undertakings which qualify as financial holding undertakings and are not engaged in management activities may be exempted from these reporting obligations (recital 12; article 29a(1)). Subsidiary exemptions remain available for undertakings included in consolidated reporting, and the Final Omnibus introduces a 12-month transition period for newly acquired subsidiaries before they must be included in consolidated sustainability reporting (recital 12b; Article 29a(1)).

The consolidated reporting scope is also reduced: parent undertakings of large groups must prepare and publish a sustainability statement only if the group exceeds 1,000 employees and EUR 450 million net turnover on a consolidated basis during the financial year (Article 29a(1)).

In addition to narrowing the scope and raising thresholds, the Final Omnibus places strong emphasis on digitalisation and reducing administrative burdens. The EU Commission will launch a central online portal providing practical information, templates, and support for companies subject to sustainability reporting. Efforts are underway to harmonise digital data formats and establish minimum technical requirements for sustainability data management systems, enabling secure and automated business-to-business data exchange. These measures aim to streamline compliance, enhance interoperability, and further reduce the administrative workload for companies operating within the EU’s sustainability framework.

The Final Omnibus keeps the CSRD obligation for companies to report on climate transition plans under Articles 19a and 29a, in line with ESRS. This is a disclosure duty: reporting undertakings must show what climate change transition plans exist (if any) and how they fit into strategy.

By contrast, the CSDDD no longer requires companies to adopt and implement such plans. Article 22 has been deleted entirely (Recital 26), removing the substantive obligation to align business models with climate neutrality goals. Therefore, under the CSDDD no longer the obligation exists to have and implement a climate change transition plan.

Nevertheless, climate planning remains relevant under other EU laws (e.g. Emissions Trading Directive, Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), Ecodesign and Energy Labelling Directive and the ECGT Directive). The deletion reduces overlap but does not eliminate the need for climate change transition planning.

The Final Omnibus text of the CSDDD

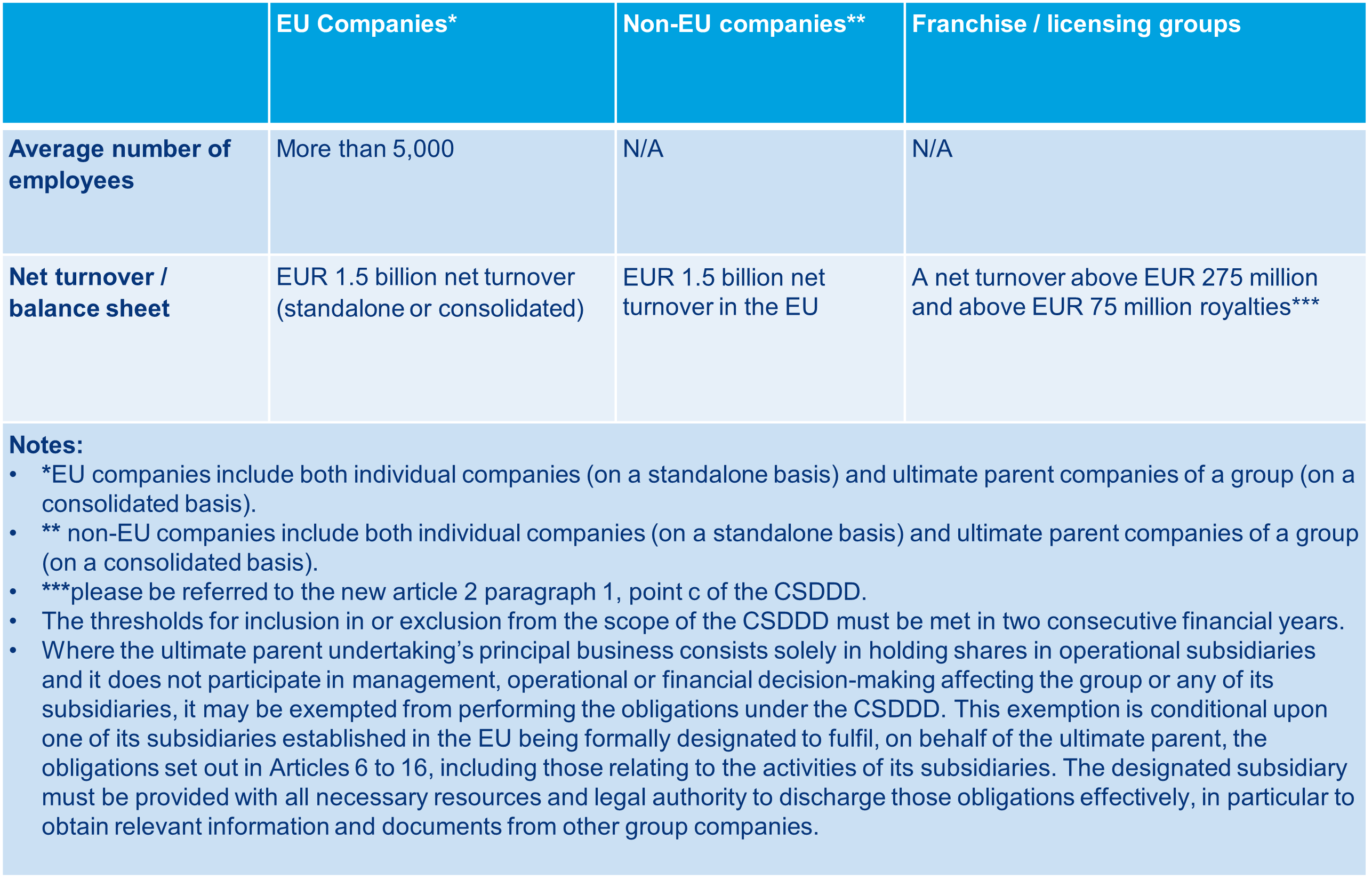

Under the final comprise text of the CSDDD, the thresholds of the CSDDD have been narrowed down.

Companies in-scope under the CSDDD

Before diving into the due diligence process under the Final Omnibus, it is essential to note two defined terms that underpin the CSDDD’s architecture:

The Final Omnibus uses this term broadly in Article 8(1) without distinguishing between direct and indirect partners for the core identification duty. However, Article 6(2)(e) introduces a practical split for contractual assurances and suspension obligations, referring explicitly to direct business partners (Articles 10(2)(b) and 11(3)(c)) and indirect business partners (Articles 10(4) and 11(5)). The distinction between direct and indirect business partners does not affect the initial scoping phase, because Article 8(1) applies broadly to all business partners in the chain of activities without qualification. In-scope companies do not need to classify partners before identifying hotspots based on reasonably available information. However, the distinction becomes relevant for compliance mechanics later in the process: contractual assurances and suspension obligations in Articles 10 and 11 are tied to whether a business partner is direct or indirect, and the text suggests that in-scope companies may prioritise assessing adverse impacts involving direct partners. In short, proximity matters for how obligations are implemented, not for determining which business partner is in scope while conducting due diligence under the CSDDD.

Defined as “facts, situations or circumstances that relate to the severity and likelihood of an adverse impact, including facts, situations or circumstances at the level of the business partner, geography, sector, operations, products and services.” This definition anchors the risk-based approach and is referenced in Article 8(2), which requires companies to take these factors into account during identification and assessment.

The Final Omnibus confirms that companies in scope of the CSDDD must take appropriate measures to identify and assess actual and potential adverse impacts arising from their own operations, those of their subsidiaries, and – where related to their chain of activities – those of their business partners (Article 8(1)). This obligation is not a one-size-fits-all exercise but is structured as a risk-based process, designed to focus efforts where they matter most and to avoid unnecessary administrative burden. With the deletion of the obligation to draft and implement a climate transition plan under the CSDDD, the due diligence obligations remains as the core obligation.

The due diligence process under the CSDDD begins with a scoping exercise, which serves as the initial filter. During the scoping exercise, in-scope companies are not required to systematically identify adverse impacts at entity level but rather are required to scope general areas. Under Article 8(2)(a) and recital 21, companies must rely solely on reasonably available information to identify general areas where adverse impacts are most likely and most severe. This high-level mapping is intended to prevent blanket questionnaires and disproportionate trickle-down effects on SMEs.

Crucially, this initial mapping during the scoping exercise must take into account relevant risk factors (Article 8(2)), as defined in Article 3(1)(u). These include circumstances at the level of the business partner (e.g., whether they are subject to comparable due diligence laws), geography (e.g., weak law enforcement), and sector or product characteristics. Integrating these factors ensures that scoping is not a superficial exercise but a targeted process that reflects severity and likelihood of harm.

Importantly, during this scope exercise phase, in-scope companies are not required to request information from business partners (recital 21 and Article 8(3)), reinforcing the principle of proportionality. In-scope companies have flexibility in judging what information is reasonably available to them.

However, the trigger – what qualifies as “reasonably available information” – remains undefined (Article 5 and 8). Does it include public data, industry benchmarks, or local-language disclosures? Until guidance or case-law clarifies this ambiguity, companies should interpret the threshold pragmatically and document their reasoning.

Once potential adverse impacts are identified, in-scope companies move to the in-depth phase (Article 8(2)(b)), obtaining accurate and reliable information about the nature, extent, causes, severity, and likelihood of the identified adverse impacts.

Here again, risk factors remain central: they guide which impacts require deeper analysis and which partners should be engaged first. Requests for information from business partners are permitted only where necessary and must be targeted, reasonable, and proportionate (Article 8(3)). For partners with fewer than 5,000 employees, such requests are allowed only if the information cannot reasonably be obtained by other means. Where multiple business partners could provide the same data, priority should be given to those most closely linked to the risk of adverse impacts (Article 8(3)(b)).

In-scope companies may also rely on alternative sources such as independent reports, digital tools, industry or multi-stakeholder initiatives, and grievance mechanisms (recital 22a), reducing duplication and administrative burden.

Prioritisation under the Final Omnibus is the mechanism that operationalises proportionality (recital 22a and Article 9). In-scope companies are not expected to address all identified adverse impacts at once; instead, they must focus first on those that are most severe and most likely to occur. Severity is assessed by factors such as the scale of harm, the number of people affected, and whether the harm is irremediable. Likelihood considers the probability of occurrence given the context and risk factors (Article 3(1)(u)). This approach allows companies to allocate resources efficiently and demonstrate compliance even if remediation is gradual. Importantly, prioritisation is dynamic: in-scope companies must review and adjust priorities as new information emerges or circumstances change.

Integrating due diligence into governance and policies means embedding these obligations into the in-scope company’s decision-making structures and operational processes. Article 10 requires in-scope companies to:

- Adopt and maintain a due diligence policy that sets out the approach, responsibilities, and escalation paths.

- Incorporate due diligence into corporate governance frameworks, ensuring board oversight and management accountability.

- Develop prevention and corrective action plans for identified risks, with clear timelines and measurable outcomes.

- Engage stakeholders selectively – limited to those directly affected and only at defined stages such as identification, plan development, and remediation (recital 24). This avoids unnecessary burden while ensuring meaningful participation.

In practice, this means due diligence is not a standalone compliance exercise but part of the in-scope company’s risk management system, influencing procurement, contracting, and strategic decisions.

The Final Omnibus removed termination of the relation with a business partner as a mandatory measure in case of an actual adverse impact in the chain of activities. In-scope companies are no longer required to end business relationships as part of last-resort obligations. Instead, Articles 10(6) and 11(7) prescribe three actions when preventive or corrective measures have failed:

- Refrain from entering into new or extending existing relationships with the business partner linked to the adverse impact (Articles 10(6)(a) and 11(7)(a)).

- Suspend the business relationship for the activities concerned, where permitted by law, and use the suspension to increase leverage (Articles 10(6)(b) and 11(7)(b)).

- Before suspension, in-scope companies must assess whether the harm caused by suspension would be manifestly more severe than the adverse impact itself. If so, suspension is not required, but the company must justify its decision to the supervisory authority.

- EU Member States shall provide – while implementing the CSDDD – for an option to suspend the business relationship in contracts governed by their laws in accordance with the first subparagraph, except for contracts where the parties are obliged by law to enter into them.

- If suspension occurs, in-scope companies must mitigate its effects, provide reasonable notice, and keep the decision under review.

- Adopt and implement an enhanced action plan:

- For potential impacts: an enhanced prevention plan (Article 10(6)(c)).

- For actual impacts: an enhanced corrective plan (Article 11(7)(c)).

These plans must be implemented without undue delay and only if there is a reasonable expectation of success. As long as that expectation exists, continuing engagement with the partner will not trigger penalties (Article 27) or liability (Article 29).

The Final Omnibus thus replaces termination as a last resort with a structured approach in the CSDDD that balances leverage, proportionality, and ongoing remediation.

The Final Omnibus removes the harmonised EU liability regime originally proposed under the CSDDD. Article 29(1) is deleted, leaving liability to national law. Member States must ensure that persons harmed by a in-scope company’s failure to comply with due diligence obligations have a right to full compensation, without overcompensation through punitive or multiple damages (Article 29(2)). Participation in industry initiatives or use of third-party verification does not exempt companies from liability under national law (Article 29(4)).

On penalties, Article 27 requires EU Member States to impose sanctions that are effective, proportionate, and dissuasive, considering the severity of the infringement and aggravating or mitigating factors. The compromise text introduces a harmonised ceiling: pecuniary penalties may not exceed 3% of the in-scope company’s net worldwide turnover (or consolidated turnover for groups). Earlier obligations to base fines solely on turnover were removed, but turnover remains a key factor.

Under the Final Omnibus, EU Member States must adopt and publish the laws, regulations and administrative provisions necessary to comply with the CSDDD by 26 July 2028 and apply those measures from 26 July 2029 (with limited exceptions, e.g., Article 16 applies for financial years starting on or after 1 January 2030).

The CSDDD also includes a review clause in Article 36, requiring the EU Commission to submit a report by 26 July 2031 and every five years thereafter. The first report will assess, among other things:

- The impact on SMEs and the effectiveness of support measures;

- The scope of the CSDDD, including whether thresholds, legal forms, or high-risk sectors need revision;

- Whether the definition of “chain of activities” should be updated;

- Whether the Annex should be modified to cover additional adverse impacts, such as governance;

- Whether climate-related rules, including transition plans and supervisory powers, need adjustment;

- The effectiveness of enforcement, penalties, and civil liability rules; and

- Whether changes to the level of harmonisation are needed to ensure a level playing field and prevent circumvention.

The review may be accompanied by legislative proposals, ensuring the CSDDD remains effective and aligned with its objectives over time.

What’s next?

With the Final Omnibus agreed upon, the legislative process enters its closing phase. The Omnibus Final Omnibus will enter into force on the twentieth day following its publication in the Official Journal of the EU and EU Member States will have 12 months to transpose it into national legislation. In the coming months, further guidance from the EU Commission is expected, particularly on enforcement, penalty calculation, and practical implementation. Companies should start assessing internal processes, reporting systems, and chain-of- activities management in light of the new requirements.

At the same time, the Omnibus remains under legal and political scrutiny. For example, the EU Ombudsman’s finding of 25 November 2025 that the Commission bypassed key Better Regulation steps – such as impact assessments and stakeholder consultations – may not invalidate the Omnibus, but it raises questions about transparency and predictability in EU lawmaking. This could lead to calls for additional safeguards or even litigation against the EU Commission, although such actions are complex and separate from the legislative timeline and implementation of the Final Omnibus.

Get in touch

As ESG legislation and litigation continue to evolve rapidly, our firm is closely monitoring these developments and the potential liability risks for companies. For tailored advice or further information about the implications of the CSRD, CSDDD, or the Final Omnibus, please feel free to contact one of our colleagues below.