Pillar Two aims to ensure that Multinational Enterprises (MNE) groups meeting the EUR 750,000,000 consolidated revenue threshold are subject to a minimum corporate taxation of 15%.

On 15 December 2022 (Directive - 2022/2523 - EN - EUR-Lex (europa.eu)), the EU Member States formally approved the EU Directive setting out a harmonized implementation of the Pillar Two model rules in the EU. The Income Inclusion Rule (IIR), the Undertaxed Profits Rule (UTPR) and the Qualified Domestic Top-up Tax (QDMTT) seek to enforce a minimum effective tax rate (ETR) of 15% on a jurisdictional basis. The IIR, UTPR and QDMTT are referred to as the GloBE Rules.

A sequence of seven steps must be followed to determine whether an entity is in-scope of Pillar Two (and benefits, as the case maybe, from a safe harbour), and whether a Top-up Tax is to be assessed to reach the minimum ETR of 15%. These seven steps are summarised below with an emphasis put on items relevant for the real estate sector. We also highlight some attention points in real estate transactions. Note that further guidance from the OECD specific for the real estate sector is still expected.

In terms of entry-into-force and compliance, the IIR and QDMTT rules entered into force on 31 December 2023 (at the earliest) in different jurisdictions both within and outside the EU, and the 2024 GloBE Information Return will have to be submitted by 30 June 2026.

-

Constituent Entities within scope

Identify groups within scope and the location of each Constituent Entity within the groupTo be in-scope, the group must establish consolidated accounts where it appears that the group’s revenue is at least EUR 750,000,000 for 2 (or more) tax years within the 4 tax years preceding the relevant tax year. Under the GloBE Rules, “revenue” is to be understood as the inflow of economic benefits arising from delivering or producing goods, rendering services, or other ordinary activities, in any event before deducting cost of sales and other operating expenses.

The entity that establishes the consolidated accounts is known as the Ultimate Parent Company (UPE). Subject to specific rules with respect to joint ventures in the sense of Pillar Two, the entities that are consolidated line-by-line are known as the Constituent Entities. Permanent establishments are treated as separate Constituent Entities.Real estate specifics

- Investment funds and REITs, as well as their subsidiaries, are excluded entities, provided that they are the UPEs and the conditions set out in the definition of these concepts are met (see below).

- The OECD has specified that net realised and unrealised gains from investments must be taken into account to determine whether the threshold of EUR 750,000,000 is reached, even if presented separately as extraordinary or non-recurring items.

- Constituent Entities include permanent establishments as defined by the GloBE Rules. The sole renting of real estate located in another country should not lead to a qualification of a PE within the scope of most treaties, even if the real estate income is taxable in the source state based on the treaties’ provision. In such a case, the provisions of the GloBE Rules related to ‘stateless PE’ should apply, which may lead to distortions in terms of allocable income.

- Services charges and taxes reinvoiced to the tenants should be recognised as profits (no compensation between profits and charges) and therefore should be taken into account to determine whether the threshold of EUR 750,000,000 is reach.

- For example, the qualification of a lease in accordance with IFRS 16 is crucial to determine the revenue of a Constituent Entity in the consolidated financial statements.

- Investment funds and REITs, as well as their subsidiaries, are excluded entities, provided that they are the UPEs and the conditions set out in the definition of these concepts are met (see below).

-

Safe Harbour

Determine if the Transitional CbCR Safe Harbour or UTPR Safe Harbour is applicable for each jurisdiction

Under the CbCR Safe Harbour generally available for financial years 2024 - 2026, the Top-up Tax due under the GloBE Rules in a jurisdiction is deemed to be zero in case one of the three tests is met:

- De Minimis Test: In the CbCR, the total revenue in a jurisdiction is less than EUR 10,000,000 and the profit (loss) before income tax is less than EUR 1,000,000;

- Simplified ETR test: the Simplified ETR is greater than or equal to the transition rate (15% for 2023 and 2024, 16% for 2025 and 17% for 2026);

- Routine Profit Test: the profit (loss) before income tax is equal or less than the Substance Base Income Exclusion as calculated under the GloBE Rules

Under the UTPR Safe Harbour (generally available for financial year 2025), the Top-up Tax under the UTPR for the jurisdiction of the UPE would be deemed to be zero provided that the UPE jurisdiction has a nominal corporate income tax rate of (at least) 20%.

The availability of a safe harbour must be assessed for the first year of application of Pillar Two. A group that has not applied a safe harbour is this first year will not be allowed to apply it in the subsequent years.

Real estate specifics

As you will read below, the “Substance Base Income Exclusion” should rarely apply to the real estate sector, and therefore the Routine Profit Test should not be available. - De Minimis Test: In the CbCR, the total revenue in a jurisdiction is less than EUR 10,000,000 and the profit (loss) before income tax is less than EUR 1,000,000;

-

GloBE income

Determine income of each Constituent Entity

Starting from the consolidated financial statements of the UPE, the group should determine the income of each Constituent Entity as reported in these consolidated financial statements. The GloBE Income corresponds to the net result of the Constituent Entity in the consolidated financial statements of the UPE, before elimination of the intragroup transactions. It is further adjusted to take into account the differences between the accounting result and the taxable result (e.g., participation exemption regime as defined by the GloBE Rules). The GloBE Income might also be negative, and it is called an admissible loss.

Once the income of each Constituent Entity has been determined, this income is aggregated (and the admissible loss is then deducted) for all Constituent Entities established in the same jurisdiction (jurisdictional blending).

Real estate specifics

- While included to determine whether the EUR 750,000,000 is reached, unrealised gains and losses (e.g., fair value adjustments on underlying real estate assets) are excluded for the determination of the GloBE Income. The ETR, as well as any Top-up Tax, is indeed determined by reference to the realised profits.

- Important item that may lead to differences between some local GAAPs and the IFRS consolidated accounts, and hence to a (potential) low(er) ETR under the GloBE Rules: the depreciation taken on the real estate assets under local GAAP (while these assets are recorded as fair value in IFRS). Because of these depreciations, the ETR as calculated under the GloBE Rules might be (much) lower than the local statutory corporate income tax rate. This is to be verified on a case-by-case basis.

- While included to determine whether the EUR 750,000,000 is reached, unrealised gains and losses (e.g., fair value adjustments on underlying real estate assets) are excluded for the determination of the GloBE Income. The ETR, as well as any Top-up Tax, is indeed determined by reference to the realised profits.

-

Covered taxes

Determine taxes attributable to income of a Constituent Entity

Starting from the consolidated financial statements of the UPE, the group should determine the taxes attributable to the income of each Constituent Entity as reported in these consolidated financial statements. Only taxes on income are considered. It is mentioned that an income tax is generally levied on a flow of money or money’s worth that accrues to a taxpayer during a period of time. The Covered Taxes definition is then further broadened by any tax on distributed profits (e.g., withholding tax on dividends that is a Covered Tax for the distributing company) and tax imposed ‘in lieu of a generally applicable CIT’. The latter includes taxes that are not described in the main rule, but which operate as substitutes for such taxes, generally withholding taxes on interest, rents and royalties (that are Covered Taxes for the beneficiary of the income).

The amount of taxes is further adjusted by the deferred taxes. For the purposes of the GloBE Rules and the calculation of the Covered Taxes, the deferred taxes are valued at the lower of the 15% minimum rate (which is the ETR to be reached) and the applicable tax rate. Deferred tax liabilities are tax expenses of the year they are recorded (or increased) while deferred tax assets are tax benefits; the total of both give the “Total Deferred Tax Adjustment Amount” (which can be negative) that is added to the amount of taxes. A deferred tax liability therefore increases the ETR in the year it is constituted (or increased) and decreases this ETR in the year it is reversed, while a deferred tax asset shall decrease the ETR in the year of constitution (or increase) and increase the ETR in the year of reversal.

An option must be exercised as from the first submission of the GloBE Information Return for the recognition of a deferred tax asset related to the admissible loss of the year.

Subject to specific rules, deferred tax liabilities should be used (reversed) within 5 years (this reversal will lead to a decrease of the Total Deferred Tax Adjustment Amount in the year concerned) to avoid a recapture, and thus a recalculation of the ETR and potentially a supplementary Top-up Tax, in the year during which they have been constituted (or increased).

Deferred tax expenses (i.e., a deferred tax liability in the year of constitution (or increase) or a deferred tax asset in the year of reversal) with respect to items excluded from the GloBE Income (e.g., participation exemption) are excluded from the Total Deferred Tax Adjustment Amount.

Once the Covered Taxes of each Constituent Entity have been determined, these taxes are aggregated for all Constituent Entities established in the same jurisdiction (jurisdictional blending).

Real estate specifics

- Deferred taxes are extremely frequent in the real estate sector. Two major items immediately come to mind: (i) the DTL corresponding to the income tax on the latent gain on a real estate asset and (ii) the DTA corresponding to the carried-forward tax losses. These deferred taxes recognised in the consolidated accounts should be carefully reviewed as they may be adjusted (or even be useless) for the purposes of Pillar Two. Indeed, a DTL recognised in the financial statements to match commercial negotiations in real estate share deals, may not be considered for Pillar Two in case the capital gain realised (even if a DTL was granted in the price formula) is an excluded income for the purposes of determining the GloBE Income based on the Pillar Two provisions on participation exemption. The DTA also raises questions, firstly on its origin (e.g., a DTA for carried-forward tax losses of a Constituent Entity stemming from the depreciation of the real estate asset, while this depreciation is not reflected in the consolidated financial statements and thus does not impact the GloBE Income) and secondly on its effective use in the future (which is also to be assessed prior to its recognition but may evolve over time).

- Bear in mind that local dividend withholding tax is a Covered Tax for the distributing entity, and not its shareholder. This may have a positive impact for captive real estate funds, which should enjoy a (nearly) tax exempt regime subject to yearly dividend distribution. For such a real estate fund being a Constituent Entity in-scope, the withholding tax due is taken into account to ultimately determine the ETR of this Constituent Entity under the GloBE Rules. If we greatly simplify but depending on the size of the distribution compared to the GloBE income, a dividend withholding tax of 15% should be sufficient to avoid a Top-up Tax.

- Deferred taxes are extremely frequent in the real estate sector. Two major items immediately come to mind: (i) the DTL corresponding to the income tax on the latent gain on a real estate asset and (ii) the DTA corresponding to the carried-forward tax losses. These deferred taxes recognised in the consolidated accounts should be carefully reviewed as they may be adjusted (or even be useless) for the purposes of Pillar Two. Indeed, a DTL recognised in the financial statements to match commercial negotiations in real estate share deals, may not be considered for Pillar Two in case the capital gain realised (even if a DTL was granted in the price formula) is an excluded income for the purposes of determining the GloBE Income based on the Pillar Two provisions on participation exemption. The DTA also raises questions, firstly on its origin (e.g., a DTA for carried-forward tax losses of a Constituent Entity stemming from the depreciation of the real estate asset, while this depreciation is not reflected in the consolidated financial statements and thus does not impact the GloBE Income) and secondly on its effective use in the future (which is also to be assessed prior to its recognition but may evolve over time).

-

Jurisdictional Excess Profit

Determine Substance Base Income Exclusion for jurisdictional excess profitThis step aims at determining the taxable base for a Top-up Tax. The taxable base, as such, equals the GloBE Income. However, as a measure to promote employment and certain industries, Constituent Entities may deduct from this GloBE Income an amount called the ‘Substance Based Income Exclusion’ (SBIE), which is a carve-out for expenditure on tangible fixed assets and payroll costs. The tangible asset carve-out is equal to 5% of the carrying value of certain eligible tangible assets of a Constituent Entity located in a jurisdiction (subject to higher rates in a transitional period).

Real estate specifics

- Certain assets are however specifically excluded from the carve-out. This includes property held for investment, sale or lease. The reason for this is that the carve-out is intended to provide a measure of relief for MNEs that have genuine physical activities in a jurisdiction – not simply purchasing investment property. Therefore, although the SBIE seems to provide relief for real estate, companies investing in real estate will not benefit from the SBIE most of the time.

- This exclusion might influence the way the business is carried-out in a low-taxed jurisdiction. Take the example of an hotel in a tax haven. If both the operation and the real estate asset are located in the same Constituent Entity (e.g., via a franchise agreement or hotel management agreement), this entity will benefit from an SBIE on both the real estate asset and the payroll costs. On the contrary, when a Constituent Entity solely owns the real estate and leases it to the operator, this entity will not benefit from an SBIE, but the operator will. However only on payroll costs and not on the real estate.

- Certain assets are however specifically excluded from the carve-out. This includes property held for investment, sale or lease. The reason for this is that the carve-out is intended to provide a measure of relief for MNEs that have genuine physical activities in a jurisdiction – not simply purchasing investment property. Therefore, although the SBIE seems to provide relief for real estate, companies investing in real estate will not benefit from the SBIE most of the time.

-

ETR / QDMTT / Top-up Tax

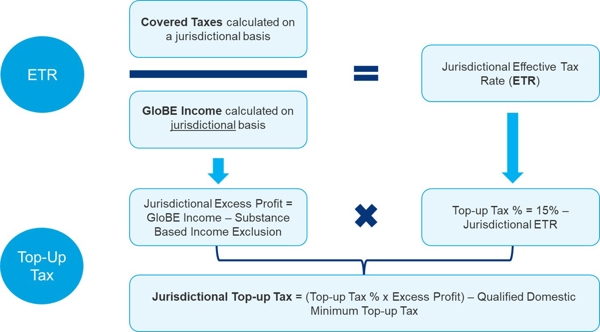

Calculate the ETR of all Constituent Entities located in the same jurisdiction and determine resulting Top-up TaxThe ETR is determined per jurisdiction by dividing the Covered Taxes by the GloBE Income. The Top-up Tax percentage is equal to 15% minus the jurisdictional ETR.

Example: For a jurisdiction, the Covered Taxes amount to 10 while the GloBE Income amounts to 100. The jurisdictional ETR therefore amounts to 10%, and the Top-up Tax percentage amounts to 5%. In this example, for the jurisdictions having implemented a QDMTT, these jurisdictions will levy an additional 5% taxation calculated on the Jurisdictional Excess Profit (see step 5).

It is noted that the basis and outcome of the preceding steps may deviate in case a jurisdiction applies a QDMTT. This is in particularly caused by the fact that jurisdictions are allowed to introduce a QDMTT that as a main rule starts from the local GAAP accounts instead of the UPE consolidated GAAP. In case a jurisdiction’s QDMTT qualifies for the QDMTT Safe Harbour, the Top-up Tax under the IIR and UTPR will be deemed zero. In the absence of a QMDTT that qualifies for the QDMTT Safe Harbour, the QDMTT is only credited against the calculated Top-up Tax and Top-up Tax may still arise under the IIR and/or UTPR. -

IIR and UTPR

Allocate Top-up Tax under IIR or UTPR

This last step is only relevant for the jurisdictions of Constituent Entities that either have not implemented a QDMTT or have not implemented a QDMTT but such QDMTT does not qualify for the QDMTT safe harbour (or such QDMTT is subject to a switch-off for instance because it does not apply in all situations, e.g., joint ventures) and the QDMTT does not allow to reach an ETR of 15% based on the UPE consolidated accounts.

Under the IIR, the UPE (or another intermediary as closest as possible of the UPE when the latter is not established in a country having implemented Pillar Two) shall bear the Top-up Tax that is attributable to it.

The UTPR, which is a fallback position that should enter into force in 2025, shall shift the burden of the Top-up Tax to another Constituent Entity of the group in case no Top-up Tax is assessed under the IIR.

The GloBE rules will apply to MNEs with a consolidated turnover of at least EUR 750,000,000. However, certain entities are excluded based on their particular purpose and status. In particular, “investment funds and real estate investment vehicles should also be excluded from the scope of this Directive when they are at the top of the ownership chain, since the income earned by those entities is taxed at the level of their owners.” More specifically:

- Investment funds that are an ultimate parent entity are excluded from the scope of Pillar Two. To qualify as “investment fund” an entity or arrangement must meet a series of seven cumulative conditions. Some of them require a specific attention. The fund must be designed to pool assets from a number of investors, some of which are non-connected. Captive funds should therefore not be able to benefit from this exclusion; that being said, captive funds should also not qualify as “ultimate parent entity”. The fund, or its management, should be subject to a regulatory regime which includes appropriate anti-money laundering and investor protection regulation. It remains to be seen what “appropriate” will mean; in any case it should be concluded that funds subject to the AIFMD and/or UCITs Directive should comply with this requirement. Other conditions relate to (i) the investment in compliance with a defined investment policy, (ii) the cost reduction or risk spreading achieved collectively by the investors, (iii) the goal of generating investment income or capital gain, or to protect investors against an event or outcome, (iv) the right to return for the investors based on the contribution made and (v) the management by professionals on behalf of the investors.

- Real estate investment vehicles that are an ultimate parent entity are excluded from the scope of Pillar Two. This exclusion benefits to REITs, defined as “a widely held entity that holds predominantly immovable property and that is subject to a single level of taxation, either in its hands or in the hands of its interest holders, with at most one year of deferral”. This definition however raises certain questions for which clarification will be needed. What does “widely held” means, is there a minimum level of floating (which is usually the case in the local regulations of REITs)? Is the condition of single level of taxation still complied with if certain activities of the REIT are taxable? In certain REIT regimes, the single level of taxation is achieved in the hands of the shareholders via a compulsory dividend distribution, but what could be the consequences if the REIT chooses to reduce its indebtedness instead of distributing or decide to reinvest instead of distributing (knowing that in certain REIT regime the reinvestment period might exceed one year)?

- To benefit from this exclusion, the investment fund or the REIT must be the ultimate parent entity (UPE). An UPE is an entity that owns, directly or indirectly, a controlling interest in any other entity (or the main entity of a permanent establishment in scope) and that is not owned, directly or indirectly, by another entity with a controlling interest in it. Based on the directive, “controlling interest” refers to an ownership interest whereby the owner is required (or would have been required) to consolidate all assets, liabilities, income, expenses and cash flows on a line-by-line basis in accordance with an acceptable financial accounting standard. In a European context, this refers to IFRS 10 (Consolidated Financial Statements) – which immediately raises the question of the exception to consolidation for investment entities who shall measure an investment in a subsidiary at fair value.

This condition might lead to quite disturbing consequences, for example in case of a European REIT (entity A) controlled by another (European or not) REIT or by a governmental entity (entity B), or in case of an investment fund (entity A) controlled by a pension fund (entity B). The entity A should be excluded from the scope of Pillar Two, provided that entity B itself benefits from an exclusion and either entity B owns (directly or through excluded entities) at least 95% of the value of entity A (which essentially invests funds for entity B) or entity B owns (directly or through excluded entities) at least 85% of the value of entity A and the latter derives substantially all of its income from dividends or equity gains (which shall not be the case in case of direct holding of real estate assets).

-

- Let’s take a captive investment fund controlled by a pension fund or by a REIT (being itself the ultimate parent entity). The investment fund shall be excluded from Pillar Two because the controlling entity is an excluded entity as well.

- Let’s take REIT A controlled by REIT B. REIT B might be excluded if it is the ultimate parent company. But REIT A shall not benefit from an exclusion since REIT A is not the ultimate parent company and, considering minimum floating requirements, REIT B is not owning 95% of the value of REIT A.

- Let’s take a captive investment fund controlled by a pension fund or by a REIT (being itself the ultimate parent entity). The investment fund shall be excluded from Pillar Two because the controlling entity is an excluded entity as well.

- Platform companies and SPVs held nearly fully by an exempt UPE and serving the investment purpose of that UPE should also qualify as excluded entities. Importantly, where the fund is excluded from consolidation obligations, it might be that in certain jurisdictions the consolidation obligation shifts to a holding entity below the fund. In such a situation, the group would not have an investment fund as UPE but that holding entity, which cannot benefit from the exclusion. If the revenue threshold is met, this holding entity will be treated as UPE for the purposes of Pillar Two. When assessing the form a fund should take, having a closer look to the accounting consolidation obligation might be a relevant point of comparison before making any decision.

Other usual suspects are pension funds and insurance companies.

- Pension funds also benefit from an exclusion for Pillar Two. This concept covers both regulated entities operating to the benefit of the public as pension funds of MNE group provided that the retirement benefits are secured or otherwise protected by national regulations and funded by a pool of assets held through a fiduciary arrangement or trustor.

- Insurance companies are large real estate investors. As a matter of principles, they are in scope of Pillar Two when meeting the turnover threshold.

Pillar Two considerations might also be relevant when comparing a share deal and an asset deal.

The consequences of an asset deal should be quite straight-forward: (i) the capital gain realised should be included in the GloBE Income, (ii) the DTL for latent gain previously recorded should be reversed (therefore reducing the ETR in the year of sale, but on the other hand such DTL has increased the ETR for the years preceding the sale), and (iii) any withholding tax upon distribution and/or liquidation of the company-owner shall be included in its Covered Taxes.

The consequences of a share deal might be more complicated.

- Firstly: the computation of the GloBE Income of the seller upon exit. The GloBE Rules provide for their own conditions for participation exemption: a capital gain benefits from participation exemption subject to a minimum participation of 10% in the benefits or voting rights of the subsidiary held for at least one year. Even if the capital gain realised upon exit is taxable in the hands of the seller (e.g., because of a “real estate rich” provision in domestic tax law), it is excluded from the GloBE Income with as a consequence the corresponding exclusion of the domestic tax from the Covered Taxes.

- Secondly: the reversal of the DTL in the hands of the seller. Even in absence of taxation of the capital gain, a seller might have recognised a ‘commercial DTL’ in line with market practices, i.e., a discount on the share price considering the latent taxable gain on the real estate. Contrary to an asset deal, the (accounting and GloBE) treatment of this DTL raises questions.

This DTL could be ‘used’ by the seller (as it has decreased the share price) but since it relates to an excluded income, it should not impact the calculation of the Covered Taxes. Since the reversal of this DTL is excluded from the calculation of the Covered Taxes, does it mean that a recapture, in the hands of the seller, of its initial constitution, must take place? Indeed, at the time of constitution of the DTL, the seller might not have decided yet whether it would dispose of the asset via a share deal.

One could also argue that this DTL still ‘exists’ in the sense that the transaction via a share deal has not resulted in a step-up in basis of the underlying real estate asset and therefore that a latent gain still exists (and have probably increased). Is the DTL then simply ‘transferred’ to the purchaser’s group (whether or not in-scope of Pillar Two) without any recapture or reversal in the hands of the seller’s group?

- Thirdly: the transfer of deferred taxes from one group to the other. Under the GloBE Rules,

- the deferred taxes are transferred from one group to the other group, with the exception of deferred tax assets stemming from admissible losses, in the same way and to the same extent as if the group had acquired the target company when these deferred taxes were created; and

- the deferred tax liability that has been taken into account to determine the Covered Taxed of the target are deemed annulled by the seller’s group and are considered as coming from the purchaser’s group in the year of acquisition.

The deferred tax asset related to carried-forward tax losses should not transferred. They should also not be maintained in the hands of the seller’s group and their reversal should therefore be recorded as a tax expense and increase the ETR, to the extent they relate to an admissible loss in the sense of the GloBE Rules (which is doubtful in case their origin is found in the local depreciation of the real estate asset).

For the other deferred taxes, the transfer only applies between two groups in-scope of Pillar Two. In case the purchaser’s group is not in-scope, then the sale of the target by the seller’s group should lead to a reversal of the deferred taxes recorded in relation to this target (and its assets and liabilities) and therefore impacts its ETR in the year of sale.

For the deferred tax liability recorded in relation to the target’s asset, it should be annulled by the seller’s group and be recognised by the purchaser’s group, but the purchaser’s group is then obliged to annul this DTL or pay the corresponding tax within the five subsequent tax years.

In the framework of any real estate transactions, each party should take a view on whether its counterparty is in-scope of Pillar Two, as this may impact the pricing, the due diligence and the drafting of the transaction documents (incl. post-closing covenants). This section only deals with ‘one-off’ transactions; the formation of a joint venture is examined in the next section. It is assumed that the target company is a Constituent Entity of the seller’s group and is not an excluded entity for the purposes of Pillar Two.

- Buyer in-scope of Pillar Two

When a buyer is in-scope, the biggest impact could be on pricing based on the buyer’s own tax position. For such a buyer, purchasing a target company in a given jurisdiction may lead to either an increase or a decrease of its ETR in this jurisdiction going-forward, as it will add a new Constituent Entity – and thus GloBE Income and Covered Taxes – in this jurisdiction.

On a more operational matter, the buyer in-scope will be careful to collect all the information required and to prepare the integration since the filing of the GloBE Information Return is due within 15 months from the end of the relevant year.

- Seller in-scope of Pillar Two

The first relevant item is the pricing, which remains a commercial negotiation. As mentioned above, the acquisition of the target might be beneficial or detrimental to a buyer in-scope, and it is the same for a seller in-scope. Moreover, the change of control over the target should result in the reversal, in the hands of the seller, of the DTA recorded for the target’s future tax benefits (e.g., losses admissible under Pillar Two). Such reversal of DTA increases the Covered Taxes and thus the ETR and should benefit to the seller.

The relevancy of Pillar Two in such a situation firstly depends on the location of each Constituent Entity of the seller’s group.

- If all Constituent Entities are established in countries that have implemented Pillar Two and have included a QDMTT in their legislation, only the tax position of the seller’s group in the jurisdiction of the target company will be relevant.

- On the contrary, in case some of the Constituent Entities are established in countries that have not implemented Pillar Two – especially in case the UPE of the seller’s group is established in such a country – the tax position of the entire seller’s group might be relevant. Indeed, the jurisdiction of the target company might be granted taxation rights under the IIR or UTPR, meaning that the target company might be liable for taxes computed on the income of other seller’s group company(ies) that are not established in the same jurisdiction.

Secondly, the number of Constituent Entities of the seller’s group in the jurisdiction of the target company is relevant. Indeed, because of the jurisdictional blending, the tax position of all Constituent Entities in this jurisdiction, including the target company, must be taken into account. The jurisdictional group may be subject to a QDMTT, with the target company being either the taxpayer or jointly liable for this QDMTT.

- The scope of the tax due diligence extends (theoretically) beyond the target company itself. Indeed, to determine whether a QDMTT will be due, the buyer should access full and detailed information about the seller’s group (at least) in that jurisdiction. It is not certain that a seller will accept to disclose this type of information; moreover, and in the first years of Pillar Two, full and accurate information might not be available yet.

- The scope of the tax due diligence might also influence the availability of a W&I insurance or a dedicated tax insurance. In most cases, the availability of such insurance shall depend on the robustness of the tax due diligence carried out; the absence of tax due diligence might render impossible the entering into such insurance. Until now, insurers are also keen to exclude Pillar Two exposures from the coverage, relying on standard exclusions for transfer pricing and secondary tax liabilities. However, in relation to other group tax provisions, we have seen insurers being willing to provide coverage under the general representations subject to specific conditions (e.g., confirmation of the seller that the rules have been complied with and commitment to assist in case of tax audit).

In this hypothesis of a seller in-scope, the transaction documents will also have to be adjusted. The most important topics to be negotiated include:

- Definition of “Taxes” should include any GloBE Rules as well as secondary tax liabilities under these rules.

- Representations & warranties, and as the case may be specific indemnities or tax covenant, should include secondary tax liabilities in case the target company would be liable for Top-up Tax of other companies.

- General exclusions, time limits and maximum liability should be carefully considered. Most of the time parties will refer to the applicable statute of limitation for claim under the tax representations, which should also cover the (longer) statute of limitation under Pillar Two. But the cap on liability might lead to negotiations or issues (e.g., if the value of the target company’s shares is imbalanced compared to a potential Pillar Two liability for the seller’s group), and the UPE might be requested to act as guarantor.

- Post-closing covenants should detail Pillar Two responsibilities: who will prepare the GloBE Information Return for the years prior to closing and the year of closing, who will take the lead in case of Pillar Two (multi-jurisdictional) disputes, which access right (to the seller’s information) should be granted to the buyer.

- The purchase price formula and intragroup debt reimbursement on closing also require attention. The locked box system is not often used in real estate transactions but will surely require a specific protection for the period between the effective date and the closing. In a situation where the target company is not legally liable for the QDMTT but shares the cost with other group companies in the same jurisdiction, one should verify that the corresponding amount is recorded as debt – and that the corresponding amount is effectively paid (as the case maybe before refinancing of this intragroup debt by the buyer).

What’s in a name

“Joint venture agreements” are frequent in the real estate sector. However, the treatment of these JVs under Pillar Two will differ drastically depending on the status of each shareholder and on their stake in the JV. In particular, an out-of-scope joint-venture partner might bear economically the burden of a Top-up Tax that is triggered by the other joint-venture partner being in-scope of Pillar Two. Several hypotheses are illustrated below.

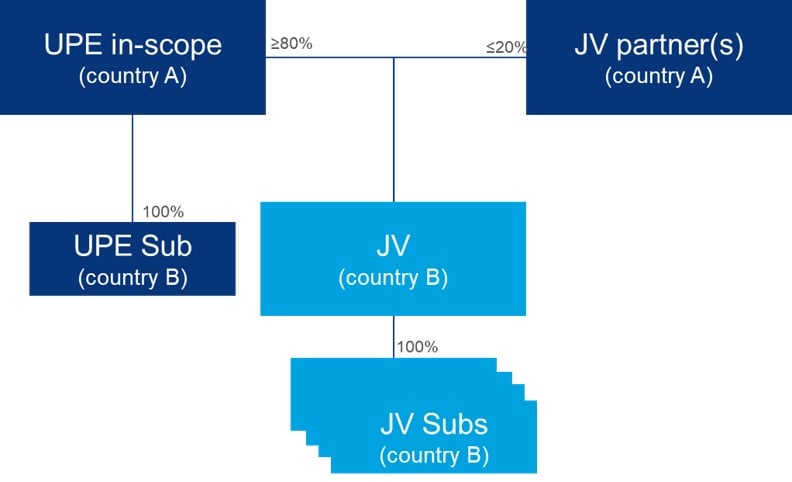

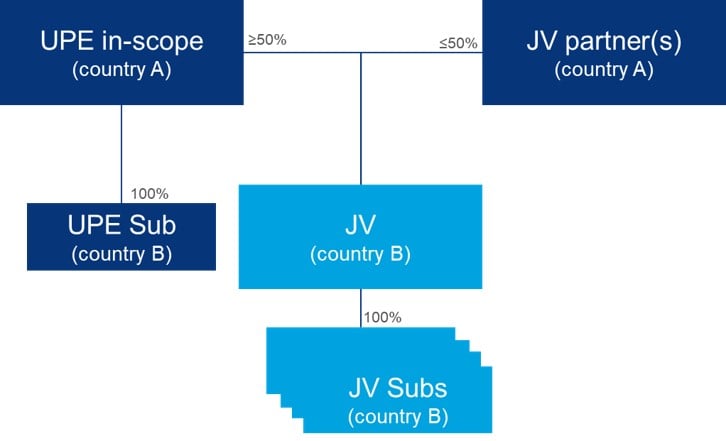

The UPE shareholder is in-scope and consolidates the JV (and its subsidiaries) line-by-line

The in-scope UPE holds an interest of at least 80% in the JV

- Country B has implemented a QDMTT

JV, JV Subs and UPE Sub are Constituent Entities in the sense of Pillar Two. To determine whether a Top-up Tax is due (to reach the 15% ETR threshold), the GloBE Income and the Covered Taxes of JV, JV Subs and UPE Sub are calculated and aggregated. In case the ETR is below 15%, a QDMTT is due in Country B.

→ Tax position of JV and JV Subs is influenced (positively or negatively) by the existence of UPE Sub, and the JV partner(s) bears (economically) the burden of this QDMTT (proportionally to its share in JV)

- Country B has not implemented a QDMTT

In absence of a QDMTT, the calculation of the Top-up Tax still follows the jurisdictional blending, but this Top-up is solely borne by UPE via the IIR, and for its share in the profits of JV, JV Subs and UPE Sub (i.e., the Jurisdiction Excess Profit of JV and JV Subs is subject to IIR up to the share of UPE in the JV; the balance of the Top-up Tax is uncollected).

→ Although the tax position of the JV and JV Subs is influenced by the existence of UPE Sub (i.e., determination of the ETR in country B), the consequences are solely borne by UPE, and not by the JV or the JV partners.

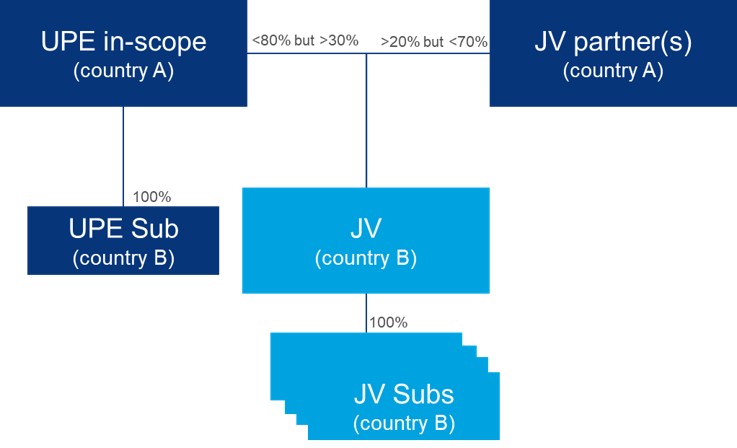

The in-scope UPE holds an interest of less than 80% but more than 30% in the JV and the JV qualifies as partially owned parent entity (POPE) under Pillar Two.

- JV, JV Subs and UPE Sub are Constituent Entities in the sense of Pillar Two. To determine whether a Top-up Tax is due (to reach the 15% ETR threshold), the GloBE Income and the Covered Taxes of JV, JV Subs and UPE Sub are calculated and aggregated.

- The Top-up Tax, either via a QDMTT or an IIR, is assessed for the full amount in the hands of the JV.

→ Tax position of JV and JV Subs is influenced (positively or negatively) by the existence of UPE Sub, the Top-up tax (if any) is assessed in the hands of JV, and JV partner(s) bears (economically) the burden of the Top-up Tax (proportionally to its share in JV).

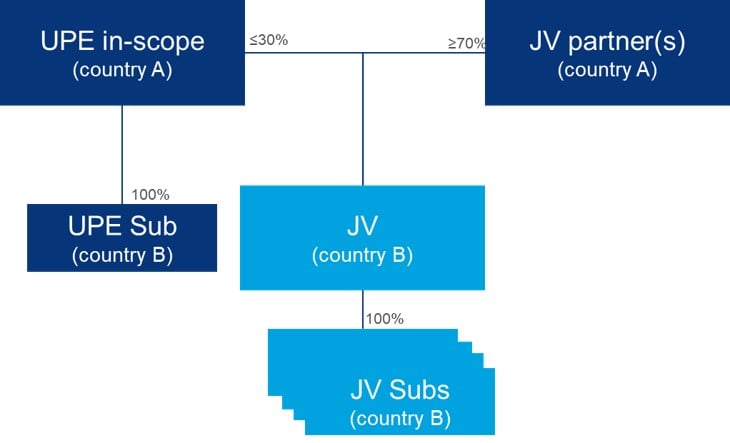

The in-scope UPE holds an interest of 30% or less in the JV (but nevertheless consolidates it line-by-line), and the JV qualifies as minority-owned constituent entity (MOCE) under Pillar Two

- JV, JV Subs and UPE Sub are Constituent Entities in the sense of Pillar Two. However, JV and JV Subs are seen as one separate group for the purposes of Pillar Two. Their ETR in country B is thus assessed separately from the ETR of UPE Sub (limited jurisdictional blending).

→ Tax position of JV and JV Subs is not influenced (positively or negatively) by the existence of UPE Sub.

- In case Country B has implemented a QDMTT, the Top-up Tax is due by JV (and/or the JV Subs).

→ The JV partner(s) bears (economically) the burden of this QDMTT (proportionally to its share in JV).

In case Country B has not implemented a QDMTT, the Top-up Tax is due by UPE via the IIR, and for its share in the profits of JV and JV Subs (i.e., the Jurisdiction Excess Profit of JV and JV Subs is subject to IIR up to the share of UPE in the JV; the balance of the Top-up Tax is uncollected).

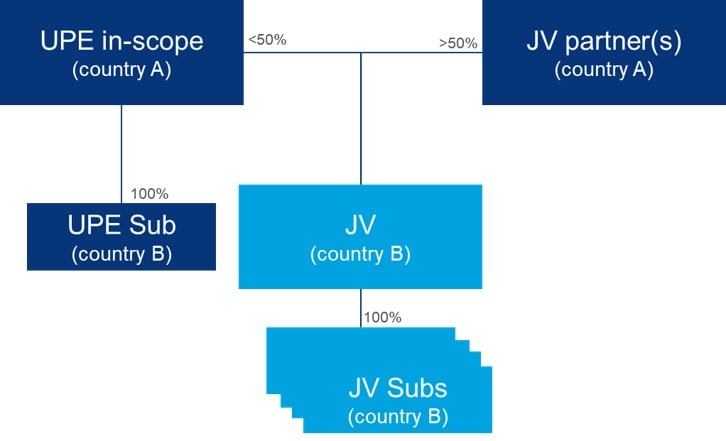

The UPE shareholder is in-scope and consolidates the JV (and its subsidiaries) based on the equity method

The in-scope UPE holds an interest of at least 50% in the JV. This is the ‘joint venture” in the sense of Pillar Two.

- The JV and the JV Subs are seen as one group for the purposes of Pillar Two. Their ETR in country B is thus assessed separately from the ETR of UPE Sub (limited jurisdictional blending).

→ Tax position of JV and JV Subs is not influenced by the existence of UPE Sub (same as for a MOCE).

- In case Country B has implemented a QDMTT, the Top-up Tax is due by JV (and/or the JV Subs).

→ The JV partner(s) bears (economically) the burden of this QDMTT (proportionally to its share in JV).

In case Country B has not implemented a QDMTT, the Top-up Tax is due by UPE via the IIR, and for its share in the profits of JV and JV Subs (i.e., the Jurisdiction Excess Profit of JV and JV Subs is subject to IIR up to the share of UPE in the JV; the balance of the Top-up Tax is uncollected).

The in-scope UPE holds an interest of less than 50% in the JV

- The JV (and its subsidiaries) fall out-of-scope of Pillar Two, for their own tax position but also to determine the tax position of the UPE (no jurisdictional blending).

Extreme example: a JV formed by three (or more) UPEs, each in-scope, and consolidated based on the equity method in all UPEs, will fall outside of Pillar Two.

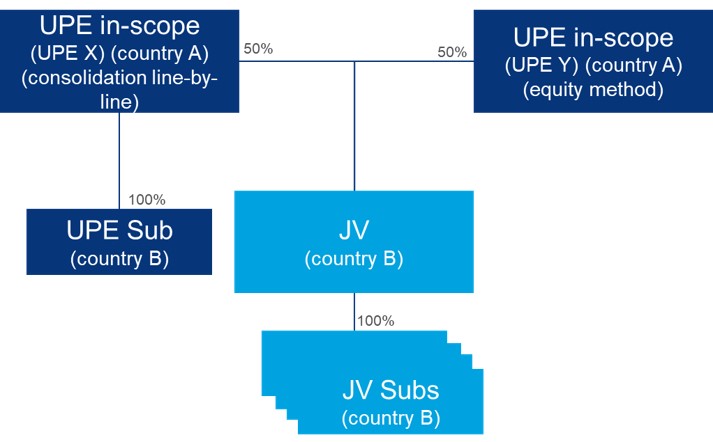

The JV is held 50-50 by an UPE in-scope that consolidates line-by-line and an UPE in-scope that consolidates based on the equity method

JV is a POPE for the UPE consolidating line-by-line (UPE X) and a JV in the sense of Pillar Two for UPE consolidating under the equity method (UPE Y).

- From the perspective of UPE X, there is a jurisdictional blending (where the results of UPE Sub are aggregated with the results of JV). From the perspective of UPE Y, there should be no jurisdictional blending.

- From the perspective of both UPE X and UPE Y, any Top-up Tax might either be assessed in the hands of the JV via a QDMTT or in the hands of the UPE via an IIR (and for its allocable share in JV).

→ The potential issue is the QDMTT. In absence of such QDMTT, each group shall make its own calculation and shall bear its own Top-up Tax via the IIR. In case of QDMTT, UPE Y might bear indirectly a share in the Top-up Tax stemming from the jurisdictional blending. The worst-case scenario is having a QDMTT for POPE but not the JVs in the sense of Pillar Two, which might lead to a double taxation.

Looking at these examples, it seems that the sole hypothesis where Pillar Two leads to a “logical conclusion” is the JV held 50-50 by two UPEs in-scope, each consolidating based on the equity method. In this hypothesis, each UPE shall bear directly (via the IIR) or indirectly (via the QDMTT), its share in the Top-up Tax, the latter not being influenced by other subsidiaries of any of the UPEs in the same jurisdiction. In all other cases, the difference in treatment, between the joint ventures and their partners, might be questioned as regard to the principle of freedom of establishment, free movement of capital and non-discrimination.

Existing joint ventures

The GloBE Rules do not provide for grandfathering clause according to which certain joint ventures established prior to their entry-into-force would fall outside of their scope. The GloBE Rules therefore have immediate effect (according to their implementation) and they will also apply to existing joint venture agreements. Parties should therefore consider their own position in such JVs and determine adjustments or re-negotiations are needed (or even possible).

Relevant provisions in joint venture agreements

Negotiating joint venture agreements will be a complex exercise, as it will first require an assessment of the qualification of the joint venture itself, and thus also of each joint venture partner. More importantly, JVs are usually set-up for a long period of time (usually 5 to 10 years, with potential extension) and therefore the situation and qualification of all parties involved may evolve over time. At first sight, the parties will be attentive to the following provisions:

- Adequate “rendez-vous” clauses to renegotiate and adapt as the case maybe the economics of the deal in case the situation of (one of) the joint venture partners would change (e.g., in case one of the joint venture partners would fall in-scope of Pillar Two during the lifetime of the JV), or the qualification of the joint venture would change (e.g., in case of share transfers), or in case the composition of (one of) the partner’s group in the jurisdiction of the joint venture (or the JV’s subsidiaries) would change (e.g., purchase or sale of companies by in-scope partner in the same jurisdiction).

- The differences between control and appropriation of profits, where the recourse to non-voting shares might impact the question on whether the JV should be consolidated line-by-line or based on the equity method.

- Any form of neutralisation of the jurisdictional blending in order for the out-of-scope partner to not share (economically) a tax burden attributable to the in-scope partner.

- Any form of neutralisation of the QDMTT burden in the hands of the JV in order for the out-of-scope partner to not share (economically) a tax burden attributable to the in-scope partner.

- Exit provisions, especially in case the parties would not be (legally or commercially) able to deal with change in circumstances.

In addition, the QDMTT that would be assessed in the hands of the JV might raise the more concerns. Depending on local implementation of Pillar Two, this could become a point of comparison (or competition) concerning the country of incorporation of the JV (but beware of substance and beneficial ownership requirements). More sophisticated solutions, like transparent or hybrid entities, might also be envisaged (but beware of other tax aspects like ATAD 2).