Like in all other sectors and markets, Covid-19 cast a large shadow over the EMEA M&A markets in 2020. While EMEA PE volume and deal value has also dropped, most notably near the end of Q1 and into Q2 as the scale of the Covid-19 pandemic became clear, PE deal activity has been more resilient compared to the general M&A market this year. EMEA-wide, total buyout value has even slightly increased compared to Q1 – Q3 2019 with the total number of deals dropping around 17%. The deal volume trend is confirmed in Belgium, with the number of deals involving financial sponsors dropping 17.3% in Q1 – Q3 2020 versus the same period in 2019. Looking at individual quarters, we notice that PE activity in Belgium was stable year on year in Q1 and Q2, with a sharp drop in Q3. While it is too early to make any definitive statements on Q4 2020, it can be expected that the second Covid-19 wave and the accompanying restrictive measures may have had a dampening effect on deal activity also in the final quarter of the year. In 2018 and 2019, transactions involving financial sponsors as a buyer or seller represented between 25 and 30 percent of the total number of transactions. Compared to 2016 and 2017 the relative number of deals involving private equity has somewhat decreased (down from 30 – 35 percent).

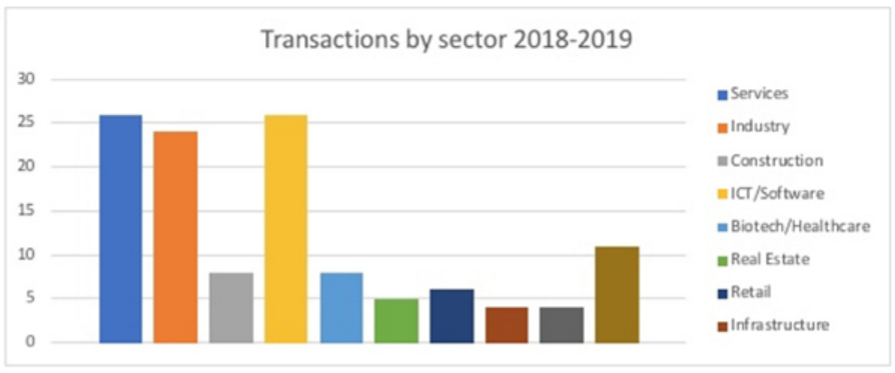

Transactions involving financial sponsors in 2018 and 2019 are broken down per sector in the below chart.

Financial sponsors usually dispose of assets through a controlled auction. Financial sponsors favour the locked box approach, allowing a clean exit and providing the possibility to distribute the consideration more quickly. The absence of any post-completion adjustment eliminates the need to hold back funds in case adjustment works against the seller. Financial sponsors are sometimes only prepared to give limited “fundamental” warranties (i.e. due existence, due authority and title to shares), in particular in secondary buy-outs.

Process for effecting the transfer of the shares

The formalities for effecting the transfer of shares under Belgian law are limited, and depend on the type of shares. Shares in a Belgian limited liability company (BV/SRL or NV/SA) are usually registered, and the ownership of these shares must be recorded in the company’s share register. Title to registered shares is evidenced by their registration in the company’s share register. Consequently, at closing, the transfer of registered shares is perfected by recording such transfer in the company’s share register. Usually parties grant a power of attorney to their local counsel to effectuate this. Shares in a Belgian NV/SA or a listed Belgian BV/SRL can also be issued in dematerialized form, although we almost never encounter dematerialized shares in M&A transactions involving a financial sponsor.

No transfer taxes payable

As a matter of principle, there is no transfer tax, registration duty or stamp duty due on the sale of shares in a Belgian company, even if the company’s sole assets consist of real estate (except for cases of abuse or simulation). In principle, stock exchange tax may be due in respect of listed securities (normally at a rate of 0.35 percent). This tax is only due upon the intervention of a professional financial intermediary, which is typically not the case in a M&A context.

Where the purchasing entity is a special purpose vehicle, financial sponsors seek to provide comfort to sellers by providing an equity commitment letter or parent guarantee from the purchasing fund. If the acquisition by the special purpose vehicle is funded through external financing, buyers will seek to provide the sellers with debt commitment letters from banks before the signing of the SPA.

In Belgium, locked box pricing mechanisms are used in almost half of the transactions. They are especially prevalent in transactions with a deal value of more than EUR 100 million. The locked box approach is the favoured approach of selling financial sponsors, allowing a clean exit and providing the possibility to distribute the consideration more quickly. The absence of any post-completion adjustment eliminates the need to hold back funds in case adjustment works against the seller. It may be problematic for a buyer to agree to a locked-box mechanism where the target is carved-out from a larger group, since it is easier for the seller to manipulate leakage from the target, for example, by hedging agreements, allocation of group overheads, current accounts and intra-group trading. Generally, however, if carefully drafted, the indemnity for leakage should provide for an adequate remedy.

In Belgium, risk is most commonly allocated between a buyer and a seller through warranties and specific indemnities. In addition, parties sometimes allocate the risk of changes in circumstances between signing and closing by including a MAC clause.

Warranties

In Belgium, the inclusion of warranties in the acquisition agreement is the most common method of allocating risk between a buyer and a seller in a M&A context. Practically all acquisition agreements contain warranties by the seller. In most cases, these contractual warranties are essentially based on a standard list. Typical standard warranties include a

warranty with respect to the target company’s accounts, the target company’s compliance with laws, and the seller’s full and accurate disclosure. The seller’s liability under the warranties is usually made subject to an exception to the effect that the seller shall not be liable for damages on the basis of facts that had been disclosed to the buyer. In Belgium, full

data room disclosures are fairly common. Alternatively, disclosures are restricted to specific disclosure schedules or letters. However, based on the requirement to carry out an agreement in good faith, the Court of Appeal of Liège (2 April 2015, see also a similar decision by the Court of Appeal of Ghent dated 18 February 2013) has decided that a buyer cannot invoke the indemnification obligation of the seller in relation to facts that it was aware of (or should reasonably have been aware of) even if such facts have not been explicitly referred to as ‘disclosed’ in the agreement. Consequently, it cannot be excluded that a Belgian judge would consider the data room disclosed even if the agreement does not explicitly provide for a data room disclosure. Taking this into account, purchasers should push for a reduction of the purchase price or a specific indemnity to cover risks that are known to it (see further below). The seller’s indemnification obligation under the warranties is, moreover, typically made subject to both limitations in time and of the amount of the indemnification obligation. A general limitation in time of the seller’s indemnification obligation for claims under the warranties is included in almost all acquisition agreements. Belgian acquisition agreements often provide for a time limit tied to a full audit cycle to give the buyer the opportunity to discover any problems with its acquisition (i.e. 18- or 24-months following completion). Time limits will generally be longer for claims for breach of certain fundamental or specific warranties: (i) for title warranties, the time limit is often tied to the applicable statute of limitations, and (ii) for tax warranties, this will typically be within a short period after the last day on which a tax authority can claim the underlying tax from the target. Limitations of the amount of the seller’s indemnification obligation usually include both a de minimis threshold for individual claims as well as an aggregate de minimis threshold (“basket”) for all damage claims taken together. As a very general rule of thumb, the market usually refers to a basket

of 1% of the purchase price and a de minimis of 0.1%. These thresholds do not typically operate as deductible amounts, and thus claims exceeding the thresholds are usually eligible for indemnification for the entire amount of the claim. As regards maximum liability, the seller’s liability is almost always capped. We often see ranges between 10% and 30% of the purchase price. The amount of the cap as a proportion of the purchase price tends to be inversely proportional to the deal value of the transaction.

Specific indemnities

Separate indemnification mechanisms are also usually included in acquisition agreements, although they are slightly less common in small transactions and competitive auctions. The use of specific indemnities has increased during the last decade. These indemnities relate most commonly to tax liabilities (ongoing or potential), but can also cover ongoing litigation, environmental pollution as well as other risks identified during due diligence. Specific indemnities are usually governed by a separate liability regime and are often not made subject to the general limitations concerning claims under the warranties. In most cases, however, indemnity claims are made subject to a separate maximum liability cap.

MAC clauses

It should also be noted that in transactions with a deferred closing, “Material Adverse Change” (“MAC”) clauses are sometimes used to allocate risks related to changes of circumstances in the period between the signing of the acquisition agreement and the closing of the transaction. Under a MAC clause, the buyer may terminate the acquisition agreement if there is a material negative change of circumstances during such period. MAC clauses are usually included as a condition precedent to closing, but sometimes also take the form of a “backdoor MAC”, i.e. a warranty by the seller regarding the absence of a material adverse change between signing and closing in combination with a termination right of the purchaser for breach of warranty. In Belgium, MACs are mostly used to protect against risks that are specific to the target company. General risks affecting e.g. the economy or the political climate in general are usually excluded. Dealmakers negotiating in times of COVID-19 should seek to tailor the definition of ‘material adverse change’ to these extraordinary circumstances, taking into account the industry and the geographic areas in which the target operates. Buyers, on the one hand, may try to obtain that a significant drop in revenue, sales or loss of contracts caused by the coronavirus crisis – the existence of which is a known event but the impact of which is hard to predict – be covered within the definition of ‘material adverse change’. Sellers, on the other hand, will attempt to exclude COVID-19, and more broadly, pandemics, epidemics and general economic conditions, from the circumstances that cause a ‘material adverse change’, arguing that the buyer is aware of the market volatility caused by the COVID-19 crisis. Buyers negotiating MAC exclusions will wish to include a ’disproportionally affects’ qualifier, thereby securing the right to still invoke the MAC clause if the target is disproportionally affected as compared to other companies acting in the same industry. In case of leveraged transactions, buyers will also try to ensure that the MAC clause in the acquisition agreement ties in with the MAC clauses in their financing agreements in order to avoid any ‘financing gap’.

In Belgium, W&I insurance policies are not the norm in M&A transactions but the practice is becoming more prevalent. In the context of transactions organized as competitive auctions and in real estate transactions, selling financial sponsors that are looking for a clean exit have started to introduce W&I insurance. In recent years, W&I insurance policies have sometimes been entered into in the context of large transactions with high deal values, although in small and medium-sized transactions they are still only rarely used.

While there have been a number of acquisitions of publicly listed companies by financial sponsors in Belgium in the past, such operations remain very unusual on the Belgian private equity market. In 2019 and so far in 2020, no public takeovers by a financial sponsor were notified to the Belgian Financial Services and Market Authority (FSMA). Financial sponsors have been active in acquiring infrastructure assets in Belgium, although such activity has been relatively modest compared to many other sectors.

The Belgian government maintains an open policy towards foreign investment. Foreign investors can freely incorporate new companies, establish subsidiaries, transfer a company or acquire shares in Belgian companies. Currently, no general system of foreign investment control is in place. However, in line with similar initiatives in other European countries, the Flemish government has adopted a decree which entered into effect on 1 January 2019. Flanders accordingly has an ex post intervention mechanism in place for investments allowing foreign investors to control public authorities or related bodies that would entail a threat for the strategic interests of Flanders. A broadening of the Flemish foreign direct investment (FDI) regime and possible measures (ex ante and ex post) is currently on the agenda of the Flemish Government. Following the COVID-19 crisis and the resulting general market volatility, the European Commission has also called upon a coordinated economic response by all member states in the field of FDI screening.

If merger clearance is required, it is standard practice to include this as a condition precedent to the closing of the transaction in the acquisition agreement. Merger clearances involving financial sponsors usually do not trigger competition issues, unless the financial sponsor has portfolio companies which overlap with the business of the target. Depending on the parties’ bargaining power, we see several practices for the allocation of the risk of merger clearance between the parties. Usually the buyer bears the risk of any required divestments, although it is not uncommon for these risks to be capped in one way or another (e.g. no obligation for the buyer to offer divestments that are disproportionate to the contemplated transaction). However, in the context of transactions organized as competitive auctions, the acquisition agreement exceptionally includes a “hell or high water” clause, whereby the buyer is obligated to take all steps to satisfy the competition authorities (including divestitures).

Most minority investments by financial sponsors are structured as straight equity investments. Convertible bonds and subscription rights that can be converted into equity are also quite common, but usually only in addition to a substantial debt or equity investment. In co-investment transactions (e.g. management buyouts), the secondary investors are sometimes granted profit-sharing certificates or shares without voting rights. In the case of straight equity investments, financial sponsors typically subscribe to a capital increase of the target company in return for shares with preferred rights on dividends and liquidation proceeds as well as certain special rights bestowing control, or at least influence, over the company. Typical minority protections sought by financial sponsors include right to information by periodic reporting, right to appoint board members, and consultation or veto rights concerning certain decisions to be taken by the board of directors or the shareholders’ meeting. Moreover, certain “exit clauses” are usually sought by financial sponsors, the most common being standstill provisions, right of first refusal, drag-along and tag-along clauses, as well as put-options. Minority investments are typically more recurring in early stage funding such as venture capital. To our knowledge, the number of minority investments undertaken by financial sponsors has not significantly increased in recent years.

Most management incentive schemes are conceptually structured as either stock option plans or free share plans, the latter being less beneficial for Belgian tax residents from a tax and social security point of view. In practice, Belgian employees are often offered options on the basis of a stock option plan issued by a foreign parent company. In such cases, these plans usually require some alteration to enable the application of the tax beneficial treatment of the Belgian tax law on stock options. Recently, we have seen a rise in tax litigation with respect to plans set up by parent companies in the past, whereby Belgian tax authorities claim that expenses in relation to the stock option plan which are cross-charged to the Belgian employer, are considered non-deductible by the tax authorities. In co-investment schemes, the shares are usually acquired directly by the managers as capital gains on shares are, in principle, exempt from personal income tax. Where future exits do not take the form of capital gains but rather give rise to dividend upstreaming, additional structuring may be required in order to try to lower or defer the tax pressure (dividends are – in principle – taxed at 30% in the personal income tax, however conditional lower rates may apply if e.g. the investment is held through a personal service company of the manager). In recent practice, the Belgian tax authorities have scrutinised carried interest structures which could allow a fully tax-free exit of the management.

Stock options receive a beneficial tax treatment, with an upfront taxation on the lump sum value of the options and in principle no taxation at exercise or, at a later stage, alienation of the shares obtained through exercising the option. In addition, stock options granted to employees are, under certain circumstances, exempt from social security contributions. This is a double advantage: no employer contributions (+/- 30% uncapped) nor employee contributions (13,07% uncapped) need to be paid with respect to this type of management incentive plans. The stock options regime is often set up in an international context, leading to possible mismatches and double taxation in the absence of a proper international structuring. The preferential tax regime applicable to stock options is different for free shares, restricted stock (units) or phantom shares, for which taxation occurs at the actual acquisition of the shares or the payment of an equivalent cash amount. Taxes are in this case due on the actual share value at the moment of acquisition. Furthermore, unlike stock options, these incentive schemes are not exempt from social security contributions. In principle, no personal income tax is due on capital gains on shares held by Belgian resident individuals, while dividends and interest received is taxed at a flat 30% rate.

At senior level, non-compete clauses are relatively common. However, in practice we see that non-compete clauses for employees are rarely activated after termination of employment: in order for the non-compete to be valid, a consideration is to be paid equal to the employee’s salary for at least half of the restrictive period if the clause is activated. Often this is not considered worth the cost. The validity conditions for non-compete clauses for self-employed managers are less stringent and non-competes (e.g. in terms of consideration) are fairly standard in these types of agreements. The non- compete period for senior managers is usually set at 12 months following termination of their employment. In exceptional circumstances, we sometimes see non-compete periods of 24 months.

There are three ways in which financial sponsors typically ensure some level of control over the portfolio company:

- Information rights – the least far-reaching method of ensuring some level of control is by imposing information covenants on the company towards the financial sponsor. This duty to inform can be periodical, topical or a combination of both.

- Nomination rights – financial investors, even when holding only a minority of the shares, usually obtain the right to nominate one or more members to the board of directors of the portfolio company. However, it is important to note that each director of a Belgian company has the fiduciary duty to act within the company’s best interest, thereby disregarding the interest of its nominating shareholder. For this reason, financial sponsors sometimes prefer to only have observer seats on the board instead of actual board seats.

- Veto rights – the most intrusive way of obtaining control as a minority investor is by requesting veto rights over specific corporate actions or material business decisions, either at the level of the board or the shareholders’ meeting. Veto rights are usually attached to a separate class of shares, which are issued to the financial sponsor. The governance of the portfolio company is usually regulated through a shareholders’ agreement and the articles of association of the company. Note that in Belgium the articles of association of a company are in principle publicly accessible.

A structure that is typically used in transactions involving a financial sponsor as acquirer, is a Dutch STAK or Belgian foundation. A STAK or foundation can be used to pool shares that are acquired in another company, for instance shares acquired by employees in the framework of an incentive plan or management that has reinvested in the newly acquired company. The STAK or foundation then issues exchangeable depositary receipts to the owner of the shares. The STAK or foundation thus enters into an agreement with the owner of the shares, transferring legal ownership of the shares to the STAK or foundation, while the original owner maintains economic ownership of the shares. In this way, the original owner of the shares (now the depositary receipt holder) will receive dividends from the acquired shares, even though he or she is no longer the legal owner of the shares (and not entitled to vote with those shares).

Although not common, we also see other types of vehicles being used from time to time to organise the purchase of company shares by a large group of employees (whether or not at market value) following which these employees are entitled to dividend income which becomes payable if case certain targets are met. The pooling vehicle is in such situations usually a blocked bank account (employees have no access) from which payments automatically occur to each employee once payment conditions are satisfied in accordance with the incentive plan. These pooling vehicles may trigger tax issues (e.g. as they represent X number of shareholders – i.e. employees holding X number of shares, triggering typical shareholder rights and obligations for these employees although they do not effectively hold these shares).

In Belgium, debt financing for private equity-backed structures is usually obtained through a traditional secured term loan facility, often supplemented by the involvement of mezzanine investors. We have seen an increase in the use of borrowing base facilities to finance working capital needs which complement the term loan facilities that are mainly used to finance acquisition costs. Loans are usually syndicated either before or after the deal is done. For post-closing syndication, one of the main concerns for lenders is establishing a mechanism for transferring loans without costs or formalities while ensuring that the full security package benefits any new lenders. It should be noted in this respect that Belgian law has improved significantly in this area, with the entry into force in 2018 of an extended security agent concept.

Under the new Belgian Companies’ and Associations’ Code, the Belgian financial assistance rules apply to public limited liability companies (NV/SA), private limited liability companies (BV/SRL), and cooperative companies (CV/SC). Under these rules, such Belgian companies may not grant any advance, loan, credit or security (personal or proprietary) with a view to the acquisition or subscription of its shares by a third party, unless in accordance with a specific procedure and under certain conditions (it being understood that such procedure and conditions are slightly more flexible under the BV/SRL and CV/SC company forms, as compared to the NV/SA company form). Any advance, loan, credit or security granted in breach of the financial assistance rules is null and void. In addition, it may trigger the civil liability of the directors (both towards third parties and the company itself). Under the new Belgian Companies’ and Associations’ Code, a violation of the financial assistance rules will, however, no longer be considered a criminal offence that can entail the criminal liability of the directors of the company. To date, the financial assistance procedures are rarely applied, since less stringent alternatives (in particular in the framework of a “debt pushdown”) are conceivable and have been tested in the past. In recent practice, such debt pushdown structures are however scrutinised by the Belgian tax administration. It remains to be seen whether the introduction of the new Belgian Companies’ and Associations’ Code will change this practice. A common way to deal with this problem is to divide the financing into various tranches whereby the Belgian company does not grant security for the respective tranche related to the direct or indirect acquisition of its shares.

While small, bilateral financings are usually based on the relevant bank’s standard documentation, the large majority of acquisition financings will be based on the LMA standard form leveraged facility agreement. As all market participants are familiar with the LMA standard form documentation, negotiation is usually limited to the commercial terms of the transaction and tailoring the credit agreement as much as possible to the structure of the deal with many of the standard provisions remaining largely untouched.

Although the level of negotiation strongly varies per transaction, the key areas of negotiation in most transactions evolves around the general undertakings (even more so for buy-andbuild companies), the financial covenants (in particular the use of equity cures and the scope of EBITDA normalisations) and financial reporting. We do see the leveraged loan market, including traditional banks, becoming more accepting of looser covenants as a result of increased competition in the market (so-called “cov-lite loans”).

In recent years, we have seen a marked increase in the use of private equity funds as sources of debt capital. This can take the form of a mezzanine or Term Loan B type participation in a larger syndicated financing or a direct financing solely provided by one or more funds. The trend can be seen throughout the debt capital market, including acquisition financing as well as real estate financing for example.