Background

The EU’s sustainability framework has undergone numerous changes throughout the course of 2025. After the European Commission published two Omnibus packages in February, the first ‘stop the clock’ package postponed key reporting deadlines for the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) (please be referred to our earlier publication). The second Omnibus package, designed to reduce compliance burdens by at least 25%, quickly became the focus of intense negotiations and has attracted significant legal scrutiny.

The European Council adopted its Final Position in June 2025 (please be referred to our earlier publication), but the process stalled in October when the EU Parliament, after initially endorsing the Final Position, unexpectedly voted against granting the JURI Committee the trilogue mandate, reopening the debate on the scope and ambition of the reforms (please be referred to our earlier publication). As a result, new negotiations took place, leading to a revised Final Position that was approved last-minute by a majority within the EU Parliament on 13 November 2025. The EU Parliament’s subsequent acceptance of this revised proposal marks a new phase in the legislative process of the Omnibus regulations.

This blog is based on the text adopted earlier by the JURI Committee of the EU Parliament in October 2025 and the amendments approved today by the EU Parliament, which together form the EU Parliament’s Final Position on the second Omnibus proposal. These elements will serve as the basis for the upcoming trilogue negotiations. Please note that minor differences or technical adjustments may still appear in the consolidated version of the EU Parliament’s Final Position. However, this blog provides an overview of the key principles and obligations as endorsed by the EU Parliament in its Final Position.

The revised Final Position of the EU Parliament on the CSRD

Companies in-scope under the CSRD

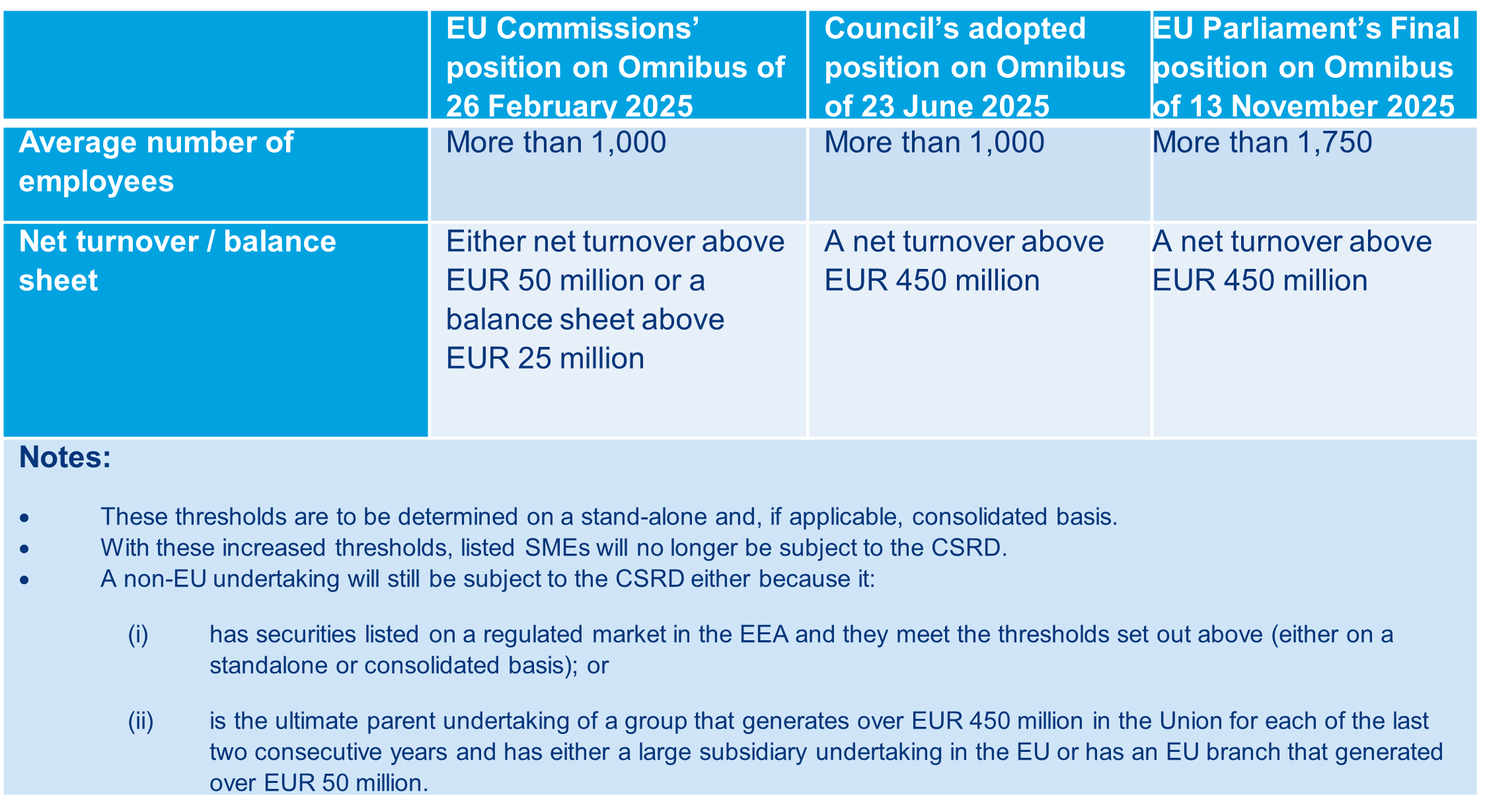

In its Final Position, the EU Parliament raises the thresholds for determining the scope of the CSRD through the second Omnibus Directive. The envisaged thresholds are as follows:

Withdrawal of the EU Commission’s mandatory reasonable assurances standards under the CSRD in the EU Parliament’s Final Position

The EU Parliament endorses the Council’s Final Position to withdraw the requirement for the EU Commission to adopt mandatory “reasonable assurance” standards for sustainability reporting (see Article 26a(3) Directive 2006/43/EC). Instead, in the Final Position, the EU Parliament proposes that only limited assurance will apply. The EU Commission is required to adopt these limited assurance standards by delegated act no later than 1 October 2026 to support limited assurance procedures. This change is intended to reduce compliance costs and administrative complexity for companies.

Empowerment and limitations in sustainability reporting standards under the CSRD in the EU Parliament’s Final Position

In its Final Position, the EU Parliament confirms the empowerment of the European Commission to adopt delegated acts establishing sustainability reporting standards for voluntary use by undertakings that are not subject to mandatory reporting requirements under Directive 2013/34/EU (Article 29ca).

These voluntary standards must be proportionate and relevant to the capacities and characteristics of such undertakings and to the scale and complexity of their activities. They shall explicitly limit the scope of information that may be requested from those undertakings and take into account legal and practical difficulties in obtaining data from the value chain, particularly from entities outside the scope of the CSRD or suppliers established in emerging markets. To facilitate consistency, the standards should also provide a structured template for voluntary reporting.

Reporting undertakings must adopt a risk-based approach, prioritising efforts to obtain information on high-risk impacts and sustainability matters commonly associated with their sector. They shall not seek to obtain from undertakings in their value chain with less than 1,750 employees and a net turnover of EUR 450 million any information beyond what is specified in the voluntary standards for undertakings that are not required to report on sustainability, except for additional sustainability information that is commonly shared within the relevant sector. Assurance providers must respect this limitation when preparing their assurance opinion.

Where information cannot be obtained due to legal or practical limitations, reporting undertakings are permitted to explain the efforts made to obtain such information, the reasons for its unavailability, and the plans to obtain it in the future. Undertakings providing such explanations shall be deemed to comply with their reporting obligations.

Until the EU Commission adopts voluntary standards – according to the EU Parliament – undertakings may report according to Commission Recommendation 2025/4984, based on the VSME standard developed by EFRAG (Article 29ca). These standards must be proportionate, use simplified language, and support flexibility and progression in disclosures. Sustainability reporting requirements under the CSRD do not oblige undertakings to disclose trade secrets, intellectual property, or know-how, in line with Directive (EU) 2016/943 (Article 29a(5a)).

Exemptions and scope adjustments under the CSRD in the EU Parliament’s Final Position

Under the EU Parliament’s Final Position, Article 19a(1) of Directive 2013/34/EU has been amended to significantly narrow the scope of individual sustainability reporting. The obligation to prepare and publish a sustainability statement at individual level now applies only to undertakings with an average of more than 1 750 employees and net turnover of at least EUR 450 million during the financial year. This represents a substantial reduction in the reporting burden for smaller entities. The same reduction in scope applies to credit institutions and insurance undertakings, regardless of their legal form.

Furthermore, ultimate parent undertakings which qualify as financial holding undertakings and are not engaged in management activities may be exempted from these reporting obligations.

Subsidiary exemptions remain available for undertakings included in consolidated reporting, and the EU Parliament introduces a 24‑month transition period for newly acquired subsidiaries before they must be included in consolidated sustainability reporting (Article 29a(1)).

Consolidated reporting scope is also reduced: parent undertakings of large groups must prepare and publish a sustainability statement only if the group exceeds 1,750 employees and EUR 450 million net turnover on a consolidated basis during the financial year (Article 29a(1)).

Climate change transition plan in CSRD in the EU Parliament’s Final Position

For the CSRD, the EU Parliament upholds the wording on the climate transition plans as set out by the EU Commission. The CSRD continues to require companies to report on their climate transition plans in accordance with the EU Commission’s standards. In contrast, under the CSDDD, the obligations regarding climate transition plans appear to have been deleted in whole.

The revised Final Position of the EU Parliament on the CSDDD

Companies in-scope under the CSDDD in the EU Parliament’s Final Position

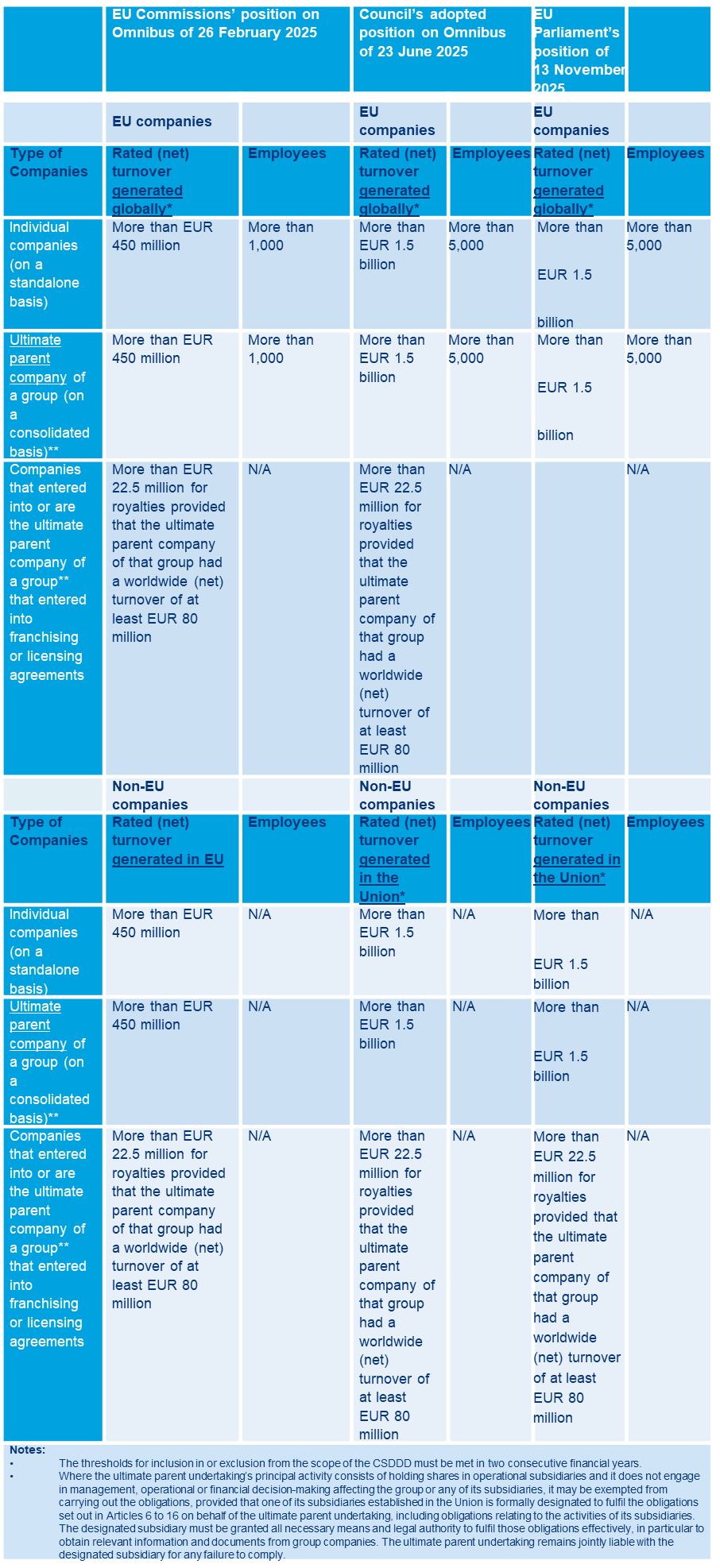

The EU Commission proposed not to amend the current thresholds under the CSDDD to be considered in-scope. The Council’s Final Position, however, includes raised thresholds and therefore a (further) reduced scope of the CSDDD. The EU Parliament aligns with this position by supporting the increased thresholds proposed by the Council, thereby agreeing to a further narrowing of the CSDDD’s scope.

Scope limitation and trigger for indirect business partners included in EU Parliament’s Final Position

One of the key amendments to the CSDDD proposed by the EU Commission in the second Omnibus is the limitation of the initial due diligence obligation in Article 5 to an in-scope company’s own operations, subsidiaries, and direct business partners. This marks a significant change from the current CSDDD: in-scope companies are no longer required to conduct in-depth assessments of indirect business partners unless they have objective, verifiable information indicating that these partners are causing or contributing to adverse impacts, such as human rights violations (see Article 5 and recital 21).

While the Council’s endorsement of this limitation was anticipated, its formulation of the exception is particularly noteworthy. Under the EU Commission’s second Omnibus proposal, in-scope companies were expected to act upon "plausible information". The Council replaced this concept with a more precise definition: "information that objectively has a reasonable likelihood of being true" (recital 21). This includes credible data from government bodies, baseline studies, third-party impact assessments, NGO reports, local community grievances, and academic research – a potentially broad range of sources of information that in-scope companies must be prepared to monitor and evaluate.

Mapping and risk-Based approach CSDDD included in EU Parliament’s Final Position

The EU Parliament builds on the Council’s Final Position by clarifying and expanding the obligation for in-scope companies to map their chain of activities. Whereas the Council required companies to identify indirect business partners using reasonably available information, the EU Parliament further specifies that this mapping must be actively employed to detect objective and verifiable information that could trigger further due diligence (see Article 8(2)(a)-(b), recital 22). In practical terms, in-scope companies are not only expected to map their direct business partners but must also systematically seek indications of risk throughout their chain of activities, including information that may be externally or indirectly available.

A central feature of the EU Parliament’s approach is the adoption of a risk-based and sectoral methodology. In-scope companies must first carry out a scoping exercise, relying solely on reasonably available information – such as public sources, previous cooperation, and secondary data – to identify areas within their own operations, subsidiaries, and relevant business partners where adverse impacts are most likely and most severe (Article 8(2)(a), recital 22). During this initial phase, in-scope companies are expressly not required to request information from their business partners (Article 8(3), recital 22).

Information request cap and exceptions

Crucially, the EU Parliament introduces a cap on information requests within the chain of activities: in-scope companies are generally not permitted to request information from direct business partners with fewer than 5,000 employees (Article 8(4)). This is a significant increase compared to the Commission’s second Omnibus proposal, which set the threshold at 500 employees, and also higher than the Council’s Final Position, which proposed a threshold of 1,000 employees. The higher threshold reflects a clear effort to reduce the burden on SMEs and further limit the spill-over effects of the CSDDD, because also any request must be targeted, reasonable and proportionate, and should focus on partners where adverse impacts are most likely to occur (Article 8(4)).

Requests for additional information from such business partners are only allowed as a last resort, and only if the necessary information cannot reasonably be obtained by other means, such as existing or secondary sources. Any such request must be targeted, reasonable, and proportionate, thereby limiting the administrative burden on smaller entities (Article 8(4), recital 22).

However, this limitation is not absolute. Where there is objective, verifiable information indicating that smaller (including indirect) business partners may be causing or contributing to serious adverse impacts – such as human rights violations – in-scope companies are required to conduct further assessments and may, under strict conditions, request information from these smaller partners, even if they fall below the 5,000-employee threshold (Article 5, recital 21). In practice, while the cap is designed to reduce the burden on smaller business partners, the exception may become the rule: whenever there are “objectively” indications of likely and severe adverse impacts, in-scope companies may still be required to seek information from smaller (indirect) business partners.

If, despite appropriate measures, companies are unable to obtain all necessary information, they must be able to reasonably explain why such information could not be obtained. In such cases, in-scope companies will not be penalised for being unable to prevent or mitigate the adverse impact (Article 8(5), recital 22).

Risk-Based due diligence under EU Parliament’s Final Position: Prioritising severe risks and ending adverse impacts

The EU Parliament also introduces significant flexibility for in-scope companies in prioritising which risks addressing first. According to Article 9 and recital 22a, in-scope companies should prioritise the most severe and most likely adverse impacts, based on the scale, scope, or irremediable character of the impact, and taking into account its gravity. Once the most severe and likely adverse impacts are addressed within a reasonable time, in-scope companies should then address less severe and less likely adverse impacts. Importantly, in-scope companies should not be penalised for any harm stemming from less significant adverse impacts that have not yet been addressed according to this prioritisation principle (see Article 9, recital 22a).

The EU Parliament’s Final Position introduces a stricter and more structured approach to ending persistent adverse impacts. Article 11(7) confirms that companies must refrain from entering into new or extending existing relationships with the business partner concerned while addressing the adverse impact. They must first adopt an enhanced corrective action plan with clear timelines and, where appropriate, temporarily suspend cooperation—provided there is a reasonable expectation of success. Only if these efforts fail or success is unlikely may termination occur, and then only if the adverse impact is severe and termination does not create manifestly more severe harm than the original impact. Companies must document their assessment, justify decisions to supervisory authorities, and take steps to mitigate any negative effects of suspension or termination, including providing reasonable notice and keeping the decision under review.

This clarification complements Article 10(4), which makes suspension an ultimum remedium rather than a mandatory measure. The previous wording “shall” has been replaced by “can,” rendering suspension optional. Before suspending, companies must consult stakeholders, assess whether no alternative exists for essential inputs, and determine whether suspension would cause disproportionate harm compared to the adverse impact. Where suspension would lead to manifestly more severe consequences, it is not required, provided the in-scope company can justify its decision to the supervisory authority. Together, these provisions mark a clear departure from the earlier approach, where termination was the default response to severe risks, and reinforce proportionality and accountability – while also increasing compliance complexity and documentation requirements.

In-scope companies are entitled to use a wide range of resources in identifying and assessing adverse impacts, including independent reports, digital solutions, industry or multi-stakeholder initiatives, collaboration, and information gathered through notification mechanisms and complaints procedures (Article 8(5), recital 22). Where, despite appropriate measures, companies are unable to obtain all necessary information regarding their chain of activities, they must be able to reasonably explain why such information could not be obtained. In such cases, in-scope companies will not be penalised for being unable to prevent, mitigate, or minimise the adverse impact (Article 8(5) and Article 9(3)).

This combination of a risk-based, sectoral approach, the cap on information requests, and the prioritisation principle reflects the EU Parliament’s intention to ensure that due diligence obligations are focused where risks are most significant, while also protecting smaller (indirect) business partners from in-scope companies from unnecessary administrative burdens and limiting the spill-over effect throughout the chain of activities. Despite these formal limitations, companies operating in high-risk sectors may still need to address risks deep in their chain of activities, reflecting the practical reach of the CSDDD.

From mandatory contractual cascading to a risk-based approach in EU Parliament’s Final Position

The EU Parliament removes in its revised Final Position the general obligation for contractual cascading throughout the value chain (see recital 22a). However, in-scope companies still could be required to seek contractual assurances from direct business partners as part of their due diligence policy, especially where risks are identified. This marks a shift from a blanket contractual obligation to a more risk-based and proportionate approach in the Final Position of the EU Parliament. The precise extent to which contractual assurances will remain a standard due diligence tool, or will be required only in specific scenarios, will depend on the final legislative text after the trilogue negotiations and its interpretation in practice.

The EU Parliament deletes the climate transition plans in its Final Position

The EU Parliament’s Final Position under the CSDDD reflects a significant relaxation of obligations for in-scope companies. Article 22 – which previously imposed requirements to align the business model and strategy with the Paris Agreement and the 1.5°C/2050 climate neutrality targets – has been entirely deleted.

As a result, there is no longer any obligation under the CSDDD – according to the Final Position of the EU Parliament – to adopt or implement a climate transition plan, nor to ensure that the business model is compatible with climate neutrality objectives. Recital 26 explains that these provisions were considered disproportionate by the EU Parliament, particularly because of the administrative burden on companies and competent authorities and the risk of legal uncertainty. They were therefore repealed in its Final Position to streamline obligations and support a more targeted and efficient implementation of the CSDDD.

According to the EU Parliament, climate-related planning and disclosure requirements should be addressed exclusively under other instruments, such as the CSRD.

Civil liability regime under the CSDDD in the EU Parliament’s Final Position

The EU Parliament has endorsed the removal of a harmonised civil liability regime from the CSDDD. As a result, liability for breaches of due diligence obligations – including those relating to business partners – will be governed by the existing national rules and procedures of each Member State (see Article 29 and recital 28). This means that the practical enforcement and possibilities for representative actions will depend on national law. In the Netherlands, for example, collective actions can be brought under the WAMCA regime, enabling representative organisations to claim damages on behalf of affected parties. Member States must nevertheless ensure effective access to justice and full compensation for victims, in line with international standards.

Administrative sanctions and penalties under the CSDDD in the EU Parliament’s Final Position

According to the Final Position of the EU Parliament, Article 27(1) of the CSDDD requires Member States to impose penalties that are “effective, proportionate and dissuasive.” When determining the nature and level of penalties, Member States must consider the gravity of the infringement and any mitigating or aggravating circumstances (Article 27(2)). Pecuniary penalties must be based on the net worldwide turnover of the company concerned. The maximum fine is capped at 5% of the net worldwide turnover, or – for certain group structures – 5% of the consolidated worldwide turnover of the ultimate parent company in the financial year preceding the decision to impose the fine (Article 27(4)). To harmonise enforcement across the EU, the Commission, together with Member States, will develop guidance to assist supervisory authorities in setting appropriate penalty levels.

What’s next on the second Omnibus?

Following the EU Parliament’s Final Position of 13 November 2025, trilogue negotiations between Parliament, Council and Commission are expected to start shortly. These talks will likely be complex given the intense debates within EU Parliament on amendments to both the CSRD and CSDDD.

At the same time, the second Omnibus – which modifies obligations under CSRD and CSDDD – remains under legal scrutiny. In May 2025, ClientEarth and other NGOs filed a complaint with the EU Ombudsman, arguing that the Omnibus breaches proportionality and transparency requirements, lacks adequate impact assessment, and undermines legal certainty for companies.

The exact scope and nature of obligations under the CSRD and CSDDD are thus still far from settled. The trilogue negotiations could lead to further changes, and the practical impact of the second Omnibus on companies operating in Europe will only become clear over time.

Get in touch

As ESG legislation and litigation continue to evolve rapidly, our firm is closely monitoring these developments and the potential liability risks for companies. For tailored advice or further information about the implications of the CSRD, CSDDD, or the second Omnibus, please feel free to contact one of our colleagues below.